Whose Athens?

Examining Graffiti and Street Art in Athens Historic Centre

19 March 2024

Anastasios Koundouris, Kalliopi Koundouri, Barbara Kondilis & Charalampos Magoulas Art, Graffiti in the City (AGC)

Fig. 1 - Hadrian's Arch in Athens by night © Barbara Kondilis

Fig. 1 - Hadrian's Arch in Athens by night © Barbara Kondilis

The famous twin Roman inscription on Hadrian’s Arch was the marker of the physical and imaginary boundary between “Two Athenses”, one of Theseus (“old” Athens), and the one of Hadrian’s (“new” Athens). It hosts the proverbial question “Whose Athens?”, one that resonates even today in a diverse context but steadfastly revolves around domination of space and the ensuing struggles and connotations of domination. One cannot fathom a city outside the premises of “space” and its varied meanings and uses, points presented in brief by the Greek non-profit collective, Art, Graffiti in the City (AGC). AGC adheres to the motto that, if you want to know more about a city, you should look at its walls. The research team examines the contemporary Athens historic city centre and its urban landscape under the light of a fierce controversy that has been raging there in recent years: dominance and possession of public space between galloping gentrification and uninhibited expression through graffiti and street art. We focus primarily on distinguishing between “unwanted” graffiti and street art and “acceptable”, most often subsidized, street art (murals). City centres have both traces of power and resistance to it (Joyce 2010; de Certeau 1988), which finds an expression in the practice of graffiti in the public sphere.

The current Municipality (as of December 2023) has so far implemented three major graffiti and non-commissioned street art eradication campaigns from selected commercial areas in downtown Athens, without any previous recording and evaluation, discarding the items erased unequivocally as “visual pollution” and “smudges” - an ideologically-charged official phrasing. Much of the graffiti and street art removed, however, was of multiple significance, aesthetic and other, such as pieces reverberating socio-political protest against permacrisis and its socioeconomic ensuing inequalities. Unconstraint gentrification, which is linked to local and international economic interests and reflects a leveling capitalist mentality, has adulterated the character of the historic center, ostracizing small businesses, making housing unaffordable for locals and mutating the city’s identity.

Athens Today

Athens is the proverbial historic city in its remaking, with the tectonic plates of opposing schemes and visions colliding. The city is a massive, ever-growing, multicultural metropolis of shifting identities, which inflame polarities, and, at the same time, nurture potential. Athens today transcends normative platitudes of the past, such as “the cradle of western civilisation”, and sterile archaeolatry. The city today poses a prolific challenge to both inhabitants and visitors: painting an oversimplified polarised portrait of it would be like amputating daring offshoots, as is the voicing of resistance on the city walls. Athens has been for some time precariously touted in the New York Times as the “graffiti capital of Europe” (perhaps rivalling Berlin), “Europe’s new mecca for street art,” and beyond the ‘renaissance’ of street art, reported as “a crisis outcry” (Greek Reporter, Aravadinos 2015). Such laurels bestowed upon the city mostly by foreign media of course entail, among other notions, the crypto-politics of consumerism, touristification and gentrification. We rather favour the perceptive definition of a city by Henri Lefebvre: “a city is the projection of a society on the ground” (Lefebvre 2007).

The multilayered decade-long “crisis” holds a strong grip not only on the capital city, but on an entire country, having a profound, identity-altering effect (Kondilis et al., 2018; Kountouri et al., 2022). The COVID-19 crisis, and what seems to be a ‘permacrisis’ is shuffling the deck and heralds new challenges as well as opportunities (Leventis 2013; Kondilis et al., 2021). Greece, in general, today is at a political crossroads, and Athens, as its capital city, resembles a political lion’s den: the right-wing governing party is usurping the space occupied by the centre after 1981, while society experiences normalisation of practices and political speech encountered in ultra-conservative political formations. These political stances serve as an ideal breeding ground for glorified folklore and stalemate archaeolatry versus the rise of the city’s fleeing multicultural identities. An added predicament is over-touristification (Smith 2022) which “threatens” ancient sites, followed by levelling gentrification; they both shape a dystopic scenery.

Fig. 2 - Athena bust marked with marker (Solonos Street, 2016) © Barbara Kondilis

Culture is governed by the idiosyncrasies and hard-core neoliberal management of the Greek Ministry of Culture, while major private institutions fill the (financial) gap, inconspicuously usurping cultural authority, as the former Mayor touted “Re-branding” of Athens part of the Municipality’s plan. Others offer a more critical stance (Bolonaki 2022, “Rebranding Athens as the Creative City of European South”), while the prioritisation and “beautification” of popular and historic areas such as Plaka and Monastiraki (Money Review article 2022) has created a bastion of gentrification. At the same time, clusters of creativity emerge, with a focus on public space, music, art, and other urban festivals, where non-profits and NGOs, and prominent individuals struggle for a piece of the action, whilst producing cultural innovation.

When It Comes to Graffiti and Street Art

The flow of expression in urban public space is continuous. As noted, the so called “dirty tagging” is vilified and demonised; political graffiti decimated more passionately, with extra fervour. While Athens has been arbitrarily touted as the “graffiti capital of Europe”, beyond platitudes and hyperboles, Athens today indeed poses as an open-air gallery: all styles/versions/manifestations of both graffiti and street art adorn the Athens city walls (on public and private space); markers, stencils, sprays, inks, and paints in a chaotic cornucopia. Quoting Dimitris Plantzos on Athens and the graffiti phenomenon, in general: “Not only in recent years, but already in the ‘merry’ 1990s, unsolicited, unauthorized, and anticanonical forms of artistic expression, such as street art, have turned Athens into a site of conflict between a centralized power promoting urban cleanliness and order and a centrifugal push for disorder and the negation of classically perceived ‘beauty’” (Plantzos 2019).

Gentrification: A Controversial Issue

As Billingham (2015) points out, modern sociological literature tends to treat the phenomenon of gentrification as a welcome process that promises growth and prosperity for societies and individuals alike, while some scholars align themselves with the findings of Slater’s analysis, according to which gentrification is identified with “rent increases, affordable housing crises, class conflict, displacement, and community upheavals” (Slater 2006: 746). Upon close look at several districts of Athens, one could observe that, while local and central authorities and other stakeholders promote major changes that will radically transform neighbourhoods and improve the quality of life of their inhabitants – without nevertheless calling this process “gentrification” – oftentimes groups of citizens form open assemblies, committees, and other initiatives try to riposte this practice, as they encounter many negative impacts on their everyday life, similar to those described above by Slater (e.g. the famous quarter of Exarcheia in the centre of Athens). Those collectives however do use the term “gentrification” implying its harmful consequences.

A Sociolinguistic Perspective

The language used by the Municipality of Athens principally regarding graffiti and non-commissioned-sanctioned Street Art is polemical, blatantly discarding, and overtly derogatory (“smudges”, “dirt”, “visual garbage”, “visual filth” to quote but a few) (Katsoudas 2019). In this vocabulary, random cases of “vandalism”, especially of monuments, are evoked, bypassing any attempt to scientifically interpret the phenomena or differentiate among different (sub)types of street art and graffiti.

According to Bourdieu (1984), ideologies serve specific interests that seek to present them as universal. With this aphorism Bourdieu aptly and succinctly demonstrates a genetic link between ideology and politics. Political discourse has a constitutive power, it forms patterns of perception and thought. This is especially evident in times of crisis. The transmitter of the message seeking to engage the judgment of the receiver uses emotive language with a particular emotional charge and utilises the mechanism of opposition to create Manichean patterns of perception of reality. Opposite camps are formed, “the good and the bad”, and any attempt at a moderate judgment or a broader approach to the phenomenon with the corresponding parameterisation is excluded. Critical discourse analysis can better showcase how the manipulation of language may violate the fundamental function of communication, by producing an authoritative monologue, as noted by Norman Fairclough (2015). Still, others note the discourse of linguistic landscapes (Scollon and Scollon, 2003) as a source of activism (Alexandrakis 2016; Pennycook, 2009) or of understanding how “superdiverse” interactions happen (Blommaert, 2013) and what we can learn from them.

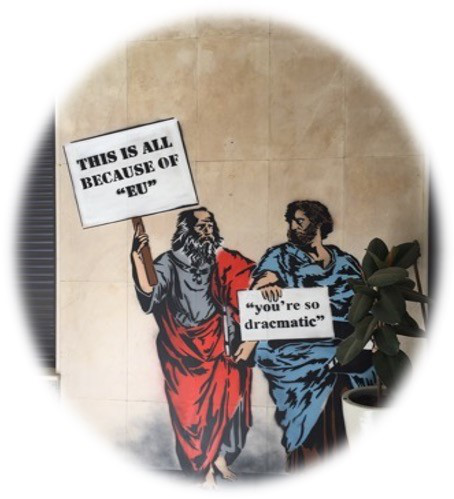

Fig. 3 - "Don’t be so dracmatic" (stencil, Omirou Street) © Barbara Kondilis

From Archaeolatry to “Archaeopolitics”

“Archaeopolitics” is a term coined by Plantzos and inspired by Michel Foucault’s “biopolitics”, of which Plantzos postulates is a “derivative”. Archaeopolitics provides a sharp tool to tackle issues concerning public space and expression in public space in the case of Athens. More particularly, the term helps contextualise the “wars for public space in Athens”, of which the massive eradication of “unwanted graffiti/ street art” is but an instance.

- “Archaeopolitics is the use of an “archaeological” mindset and form of action […] about the classical past, so that one controls the present” (Plantzos, 2019, 11. Translated from Greek by Kalliopi Koundouri);

- “In the early twenty-first century Greece archaeopolitics is […] activated in a disorienting fashion, through classifications and eliminations, so as to map the national future arbitrarily, but also almost inevitably” (ibid);

- Archaeopolitics is “idealising the past”: “as a set of politics that instrumentalizes discourse about the past, so as to control any discussion about the present, and, of course, program the future” (87).

"Let’s Clean Up the Mess”: Three Major Campaigns (and Countless Smaller Ones, Daily) to “Purify” Athens from “Dirt and Smudge”

The Municipality of Athens has launched since 2019 (Kampouris 2019) and completed: a) an escalating campaign for erasing “dirty tagging” and random graffiti from particular areas of the city, such as walls across the bustling high street of Patission towards Alexandras Ave (a total of more than a kilometre long and 3.5 meters in height) in 2020;

- b) the Ermou (another high street) Campaign (1700 m2) in 2021;

- c) the “cleansing” of 300 m2 of the ancient walled precinct of the Agora and a part of the façade of the Stoa of Attalus (anti-graffiti campaign) in 2022.

It is worth mentioning that the Municipality of Athens is supported by sponsorships from private companies (who sell, among others, anti-graffiti paints, films and other related materials), and by institutions run by Diaspora Greeks, such as The Greek Initiative.

(Re-) Claiming the City but for Whom?

As we delve into the deeply-rooted motives behind the implementation of the aforementioned policies, we register a lack of centralised policies such as a structured response to current precarities and global/local challenges in coordination with a striking lack of coordination between central and local government. We perceive that “Archaeopolitics” go hand-in-hand with neo-conservativism and blatant nationalism that taunt contemporary Greece. Regarding the case of graffiti (massively political) and street art in public urban space, we observe two forms of expression that both protest and raise questions in their unadulterated spontaneity. On the one hand, there is an attempt towards the city’s re-branding, orchestrated principally by the municipality of Athens, evolving mainly around platitudes such as “archaeolatry” and glorification of the city’s classical and neoclassical past. While on the other, we believe the central government seems to be missing the point, by discarding graffiti and its association with tourism, altogether. An indicative demonstration of such a discard can be traced in the term “Graffito Tourism” as presented in the related article in LIFO magazine year 2018 article which emphasizes the lack of aesthetic value of the ‘dirty’ graffiti left behind by visiting tourists. In contrast to this mindset, we implore that the city’s graffiti landscape massively incites visitors to share and relish this vast visual depository. Graffiti and street art, in our view has become a valued touristic product eluding the state-crafted cultural ‘policy’, and is inseparable from the city’s cosmopolitan, multicultural, and fluid identity.

Fig. 4-5 - Street art and tags (Technopolis) © Barbara Kondilis

Counting Losses

Could we be standing in the face of an unfolding scheme, through drafting and assembling a twisted, new local folklore (e.g. at the gradually gentrified neighbourhood of Exarcheia), supporting an invented, commoditized “local character”, devoid of any authentic cultural context (such as the resilient social bravado still very much alive there)? Massive public works, like the much-disputed “remaking” of the historic Exarcheia Square and the forced building of a metro station right at its very heart, are taking centre stage in the dispute around “expression” within the surrounding public space. Another way to control and exploit public space is though indirect ghettoisation, reserving graffiti clusters for impoverished areas, such as parts of Metaxourgeio, Votanikos, Petralona, until in due time they too will be gentrified (the Petralona region is already experiencing this). Conclusively, it is mainly through the Municipality’s official anti-graffiti campaigns that the city has experienced a silencing of many opposing voices that “went public” on the walls, escaping the auditoriums and conference rooms. One street art work by Barba Dee of a Venus de Milo (on a neoclassical entryway at Hafteia) “mocking” the galloping consumerism found in megastores across the street, was created in 2020, and was erased in the same year by the municipality; yet, it can be found ‘for sale’ on a product site (2020 Venus image). Such an action can be viewed as an attempt to extinguish public memory, which is inexorably intertwined with taming political effervescence.

Conclusions

Examining graffiti requires a broader semiotic approach helping to understand the symbolic connections, the cultural background of human action and the social processes that take place. Approaching graffiti as part of the linguistic and wider semiotic landscape can be the key to a broader understanding of urban culture, changing social conditions, reforming identities, and cultural ferments of the epoch in which we live.

The “graffiti wars” exemplify a latent, far more intense contest between neoliberal political forces in culture, and an amalgam of alterities which are propelled, on many occasions, by reactionary incentives. In tandem with adverse centrally planned policies, graffiti in Athens could be studied as part of manifold resistance movements (against gentrification, impoverishment etc.). Decentralising-localising decision-making is indeed a herculean task that involves giving voice to locals (communities, NGOs, cooperatives, businesses etc.), engaging tourists and passers-by, while bringing together (through social media, cooperatives, use of new technologies) local communities and entities. Partnering with historical cities marks the next prominent step of the AGC projects towards their maturity. The city of Athens is reflective of the current stakes, conflicts, controversies, and dynamics that exist on a social and political level for the historian of the future. We aspire to contribute to viable, democratic, and inclusive policies, principally because the conflict about the “talking walls” of Athens is a synecdoche for the “war” and “opportunity” for public space.

References

Alexandrakis, Othon. 2016. “Incidental Activism: Graffiti and Political Possibility in Athens, Greece.” Cultural Anthropology 31, no. 2: 272-96. https://doi.org/10.14506/ca31.2.06

Aravadinos, Toni. “Graffiti in Athens: Street Art Renaissance or Crisis Outcry?” Greek Reporter, November 29, 2015.

Athanasiou, Maria. “Graffiti: Street art has its own history” [Graffiti: Η τέχνη του δρόμου είχε τη δική της ιστορία] Kathimerini, September 20, 2021. https://www.kathimerini.gr/k/k-magazine/561505219/i-techni-toy-dromoy-eiche-ti-diki-tis-istoria/

Billingham, Chase. 2015. “The broadening conception of gentrification: Recent developments and avenues for future inquiry in the sociological study of urban change.” Michigan Sociological Review, 29, (Fall): 75-102. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43630965

Blommaert, Jan. 2013. Ethnography, superdiversity, and linguistic landscapes: Chronicles of complexity. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

Bolonaki, Styliani. 2022. “Rebranding Athens as the Creative City of European South. The Contribution of Documenta 14. A Critical Approach.” European Journal of Creative Practices in Cities and Landscapes 5, no. 2: 186-203. https://doi.org/10.6092/issn.2612-0496/13537

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1984. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Boyd, Denise Roberts, and Helen Bee. 2015. Lifespan Development, 7th ed. USA: Pearson.

de Certeau, M. 1988. The practice of Everyday Life, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

E-Kathimerini (n.a.). 2020. Central Athens street purged of graffiti after 20-day cleanup campaign. https://www.ekathimerini.com/news/260071/central-athens-street-purged-of-graffiti-after-20-day-cleanup-campaign/

Fairclough, Norman. 2015. Language and Power, 3rd ed. Routeledge.

Giannakopoulou, Georgia. 2015. “Modern Athens: Illuminating the ‘Shadows of the Ancestors’.” 33, no. 1: 73-103. Project MUSE. https://doi.org/10.1353/mgs.2015.0011

Joyce, Patrick. 2010, January 15. “The state, politics and problematics of government.” The British Journal of Sociology 61, s1 Special Issue: 305-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01291.x

Kampouris, Chris. 2019. “Athens Authorities Continue Anti-Graffiti, Cleanup Campaign in City Center.” The Greek Reporter, October 7, 2019.

Karapapa, Stavroula. 2019. “Copyright protection of street art and graffiti in Greece: intellectual property and personal property in conflict?” In The Cambridge Handbook of Copyright in Street Art and Graffiti, edited by E. Bonadio, 239-254. Cambridge University Press. DOI: 10.1017/9781108563581.016

Karathanasis, Pafsanias (2014), ‘Re-image-ing and re-imagining the city: Overpainted landscapes of central Athens’, in M. Tsilimpounidi and A. Walsh (eds), Re-Mapping ‘Crisis’: A Guide to Athens, Ropley: Zero Books, 177–182.

Katsoudas, Akis. 2019. “Athens cleans up after the illegal graffiti and its scribbles.” [Η Αθήνα καθαρίζει από τα παράνομα γκράφιτι και τις μουτζούρες της]. LIFO, April 22, 2019. https://www.lifo.gr/now/greece/i-athina-katharizei-apo-ta-paranoma-gkrafiti-kai-tis-moytzoyres-tis

Kondilis, Barbara, Kakampakou, Chrysoula, Nikolaou, Anna, and Theodora Kalapothaki. “Viewpoints of Vandalistic Style Graffiti in Crisis-Ridden Athens: Implications for European Reform.” Paper presented at Europe in Discourse: Agendas of Reform, 2nd International Conference, Hellenic American University, Athens, Greece, September 21-23, 2018.

Kondilis, Barbara, Koundouri, Kalliope, Koundouris, Anastasios, Ivrou, Vasiliki, Plemmenou, Eleni, and Alexandra Kourakou. “Graffiti and Health Literacy in the COVID-19 Crisis in Greece and in Europe.” Paper-presentation presented at The 1st Global Health Literacy Summit virtual conference. Taipei, Taiwan, October 3-5, 2021.

Koundouri, Kalliope, Kondilis, Barbara, Koundouris, Anastasios, and Charalampos Magoulas. 2022. “Tagging, ‘Aesthetic’ Terrorism and Related Issues in Athens, Greece.” International Journal for Research in Social Science and Humanities 8, no. 2: 01-13. https://gnpublication.org/index.php/ssh/article/view/2033

Lefebvre, Henry. 1977. “The Right to the City and its Urban Politics of the Inhabitant" [Δικαίωμα στην πόλη – Χώρος και Πολιτική translated by Panos Tournikotis & Claud Loran]. Athens, Greece: Koukida Press, 2007.

Leventis, Panos. 2013. “Walls of Crisis: Street Art and Urban Fabric in Central Athens, 2000–2012,” Architectural Histories, 1, no. 19: 1-10. http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/ah.ar

Loukaki, Argyro. 2021. Urban Art and the City: Creating, Destroying, and Reclaiming the Sublime. Routledge publishers.

Nomeikaite, Laima. 2017. “Street art, heritage and embodiment.” Street Art & Urban Creativity, 3, no. 1. https://doi.org/10.25765/sauc.v3i1.62

Pennycook, Alastair. 2009. “Linguistic landscapes and the transgressive semiotics of graffiti.” In Linguistic Landscape, edited by Elana Shohany, and Durk Gorter. Routledge.

Plantzos, Dimitris. 2019. “Athens remains; Still?” Journal of Greek Media & Culture 5, no. 2: 115-24. https://doi.org/10.1386/jgmc.5.2.115_2

Plantzos, Dimitris. 2019. “We owe ourselves to debt: Classical Greece, Athens in crisis, and the body as battlefield.” Social Science Information, 58, no. 3: 469-92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018419857062

Scollon, Ron, and Suzie Wong-Scollon. 2003. Discourses in place: Language in the material world. London: Routledge.

Smith, Helena. “ ’Red lights are flashing’: Athens tourism explosion threatens ancient sites.” The Guardian, November 29, 2022. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/nov/29/red-lights-are-flashing-athens-tourism-explosion-threatens-ancient-sites

Taylor, Myra., Cordin, Robin, and J. Njiru, 2010. “A twenty-first century graffiti classification system: A typological tool for prioritizing graffiti removal.” Crime Prevention & Community Safety, 12, 137– 55. https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2010.8

Tsamantakis, Xaritonas. 2017. The History of Graffiti in Greece, volumes 1 and 2, Athens, Greece: Futura Publications.

Tulke, Julia. 2017. ‘Visual encounters with crisis and austerity: Reflections on the cultural politics of street art in contemporary Athens’, in D. Tziovas (ed.), Greece in Crisis: The Cultural Politics of Austerity, London and New York: I.B. Tauris, 201–219.

Anastasios Koundouris is a graduate of the Department of Philology of the National Kapodistrian University of Athens. He received his PhD in History of Education from T.E.P.A.E.S. Rhodes University of the Aegean. He was a scholarship holder of the State Scholarship Foundation (IKY).

Kalliopi Koundouri holds a PhD in History of Art from the University of the Aegean. She is the co-recipient of Chart award (Birkbeck, University of London). Her experience includes serving as a scientific associate at the Museum of Modern Greek Art in Rhodes, and is engaged in art curation, and various arts projects. She is currently working as a philologist for the Greek public education system, and she is adjunct faculty at the Hellenic American University.

Barbara K. Kondilis is a counselor, researcher, clinical social worker, educator, and trainer. She is experienced in the mental health field since the mid 1990s, and she is a member of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control & Prevention “Prevention Specialist Service” (1999-2002). A recipient of a Marie Curie Reintegration Grant, Founder of the first Toastmasters Club in Greece, Co-Founder and Board member of the Hellenic Scientific Society for Health Literacy, and President of AGC since 2022. She is completing her PhD dissertation in Professional Language and Communication from Hellenic American University.

Charalampos Magoulas studied Philosophy and Sociology in Athens, and Language Sciences in France (PhD). He teaches Philosophy, Methodology of Research and Teaching Literature at the University of Nicosia and Philosophy and Theatre at the Open Hellenic University. Author of several books, he served in seven European and International Research Programmes and published in collective books on Semiotics, Philosophy and Sociology in English, French, Spanish, and Greek.