‘Dangerous’:

C. P. Cavafy and the Art of Queer Survival

8 February 2023

Billie Mitsikakos University of Oxford

In the second conference of the Cultural Analysis Network Greek Studies Now, entitled Greek Studies Now: Local Cases, Global Debates (Amsterdam, June 2022), my paper ventured to bring together and explore three concepts: danger, defined as exposure to threat and precarity, queer survival, and the aesthetic. I aimed to show how these three concepts come to frame Constantine Giannaris’s queer biopic Trojans. A Life of C. P. Cavafy, released in 1990, and Cavafy’s poem ‘Τα Επικίνδυνα’/‘Dangerous’ (all translations used in the text are Daniel Mendelsohn’s, in Cavafy 2009). Contrary to the usual structure of conferences in Modern Greek Studies, in which queer presentations, when (or even if) admitted, are treated as sprinkles of colour – in the best-case scenario, dispersed within the final programme and thus stripped of their potential to get in dialogue with each other and attempt radical disciplinary and epistemic interventions – in Amsterdam I had the rare chance to participate in a queer panel under the banner ‘Queering Greece’. Hence my desire to acknowledge and cherish the safe space provided, the feelings of not only being able to speak without having to ventriloquise the established academic vernacular but also of being heard and taken seriously. These feelings of connecting and interacting with my peers and seniors in search of different ways of being together and meaning differently and without fear, constituted a positioning moment for my shaping as a researcher and for the future undertaking of my DPhil project.

‘Now that everything is dangerous…’

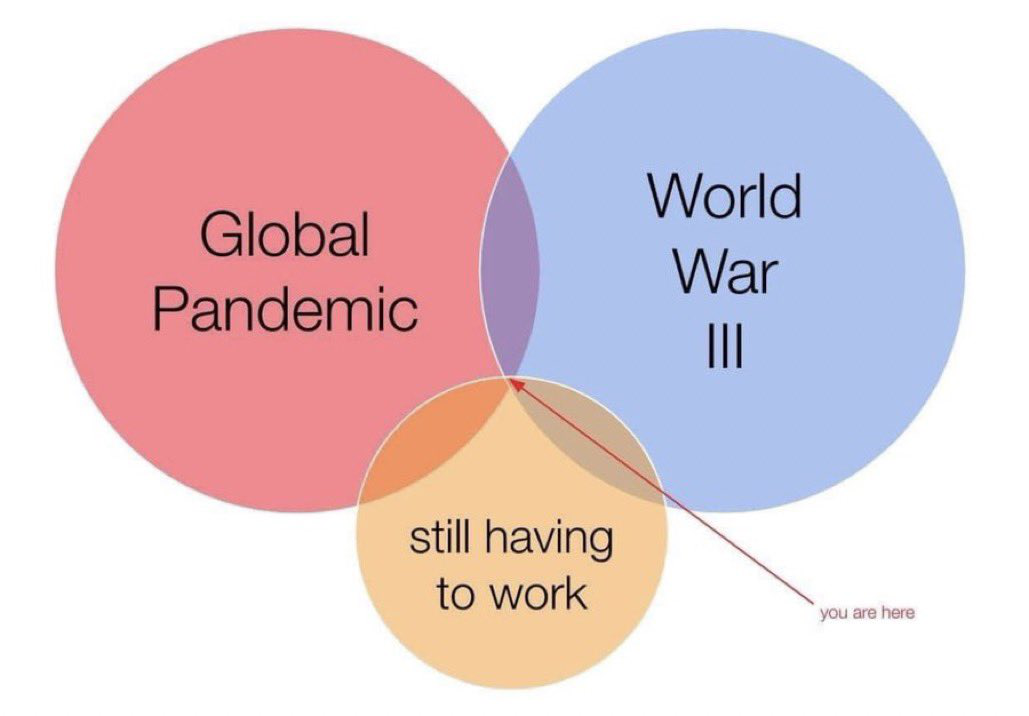

When the war in Ukraine erupted in February 2022, and while still in the midst of the COVID pandemic, one of my colleagues said: ‘Everything is more complicated, now that everything is dangerous’. Later that day, I bumped into a meme featuring a Venn diagram (figure 1) which I am using as a steppingstone to broach the following idea: How can an intensification of our endangered predicament set in motion a critical reflection on the pre-determined and overdetermining scripts that expose our existence to harm and at the same time frame, regulate, and coerce it according to the degrees of exposure to danger? Christopher Robinson once memorably described C. P. Cavafy as the poet of the Venn diagram par excellence in the sense that ‘[he] accepts the way in which the fragmentation inherent to experience can be reassembled into personal and group meanings’ (Robinson 2005: 276). What if this interplay between experience and meaning is a disobedient renegotiation of precepts imposed on being and knowing by throwing into relief the overlapping areas of the Venn diagram within which the subject emerges?

Figure 1 (https://twitter.com/marklewismd/status/1497347004967522308. Accessed 09/10/2022)

When we ask: ‘Who is apt to survive?’, the answer is: ‘Whoever does normativity best’ (Bateman 2017). That is, whoever is recognised and destined to survive as a subject within the script of heteronormativity, whoever performs the script satisfactorily or adapts adequately to its demands and reconfigurations. If, trusting Sedgwick (1991, 1993), the fundamental wish of the structures of heterosexual domination is that queer people not be, if the baseline condition of queer existence is its susceptibility to danger, and if every queer has a story about how they survived, how have queers extracted sustenance from cultural texts, icons, and peril itself? Wayne Koestenbaum (1994) and Neil Bartlett (1988) have cast light on how cross- and overidentification, in their cases with opera divas and Oscar Wilde, contributed to their crafting of a queer self and shored up their survival. Giannaris himself declared that he tried to interpret his own life through Cavafy (Sawwas and Giannaris 2013: 136). I am arguing that engaging with queer Cavafy constitutes a survival strategy inasmuch as it involves a critical and creative working on and of the queer self. In this light, I am reading back into Cavafy in order to examine how the poet himself proposed an aesthetics of existence, and an art of queer survival, stemming from the maximisation of exposure to danger in order to carve out a subject position capable of uttering radical demands. By doing so, I am suggesting that Cavafy is not only an anchor for queer survival but also that future queer subject formation rescues Cavafy: intriguingly, (queer) Cavafy both foresees and is foreseen by the future, as Maria Boletsi (2018, 2022) has deftly put it.

Within this context, the aesthetics of the self and of existence play a pivotal role. During the 1980s, Foucault (1994) shifts the focus from the politics of revendication of rights warranting queer survival to the affirmation of queer survival, which squared with his propelling an enterprise of the ‘aesthetics of existence’. It amounts to devising a homosexual lifestyle as an art of life, premised on the pleasurable and ascetic, that is, the persistent and ethical, in the Foucauldian sense, work on the self, a relational system that would result in new relational and affective networks of virtue for the transformation of society. Reading Foucault, Butler (2004) tethers self-stylisation to critique as an art of voluntary insubordination that stretches the ontological and epistemological limits established by power structures with regards to what is and can be known as a subject. This kind of self-stylisation, driven by an unregulated contact with danger, I would wager, constitutes an art of the self and of existence enabling a critique which brings the contemporary ordering of being to its limit, takes issue with limitation and, by questioning it, asserts the very right to challenge predetermined terms of ordering being and knowing.

Pensive bodies, surviving desires, and Giannaris’s Trojans

Giannaris’s aim in the Trojans is twofold (Sawwas and Giannaris 2013: 135): on the one hand, to create a film running counter to a ‘sanitised’ vision of Cavafy that had been proposed by the Greek philological establishment (represented, in the eyes of Giannaris, by Cavafy’s main editor, G. P. Savvidis). According to Giannaris, Savvidis and other Greek critics had tended to efface Cavafy’s queer specificity by veiling it with generalisations on desire. On the other hand, Giannaris’s purpose with the Trojans was to deal with the undoing and decimation of the queer community, and of his loved ones, in London during the HIV pandemic, with cases rising steadily among loved ones throughout the 1980s. From the outset, a reflection on and an intervention in the survival of queer Cavafy within the broader Cavafy signifier intersects and interacts with the stakes of survival of Giannaris’s queer community. This critical stance is also translated into Giannaris’s formal choices: Dimitris Papanikolaou (2015) has observed that Giannaris’s camera follows a pensive movement, resting on photographs, personal and archival material, as well as on faces, stretching time (‘a foregrounding of time passing’, 292), enabling a possessive gesture over the material and a contemplation on the medium of the film itself. Drawing on Bellour, Papanikolaou has argued that this pensive spectator, whom Giannaris fashions and prompts, is a necessary subject position and modality of engagement for queering the genre of biopic, for telling a queer (hi)story, for yoking biography to autobiography, and for doing non-normative identity and community politics, especially at a time of crisis. By bringing into focus the biopic’s segment on the Alexandrian young men, I am expanding on this insight and I am proposing the working hypothesis that this pensivity is also embodied by Giannaris’s protagonists: within the queer ecology of the biopic, their pensivity is translated into the staging of lingering bodies as well as into the young men’s own lingering on specific objects and figures. I would claim that this ‘body pensive’, meaning the body that takes its time to present itself persistently in an abandonment that not only facilitates contemplation but is also contemplative itself, as well as the body taking its time to focus on and cathect other bodies, has stakes in the fashioning of critical, aesthetically crafty, and risky queer personhoods and communities.

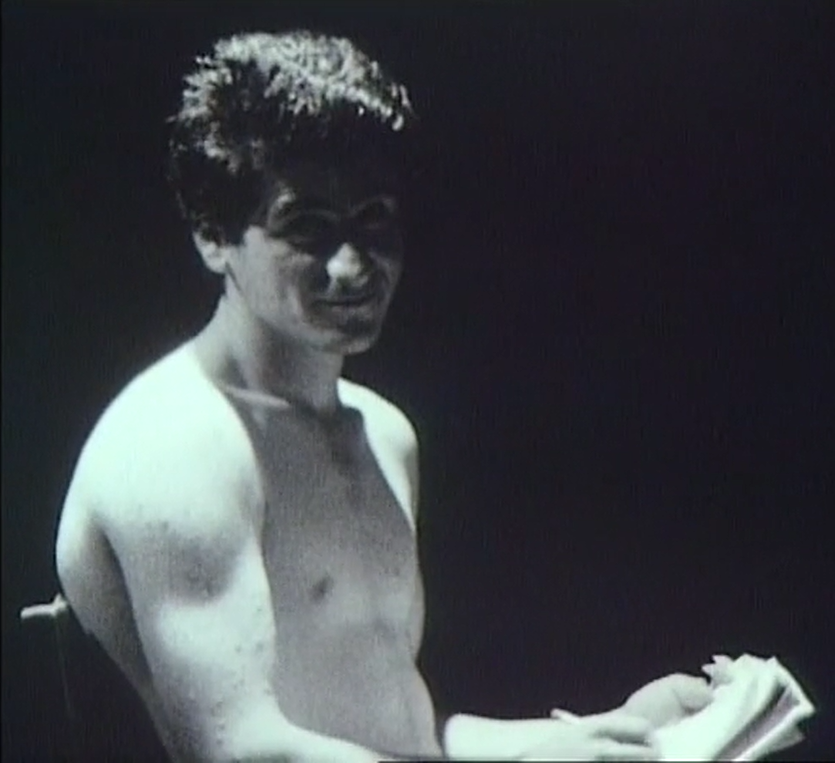

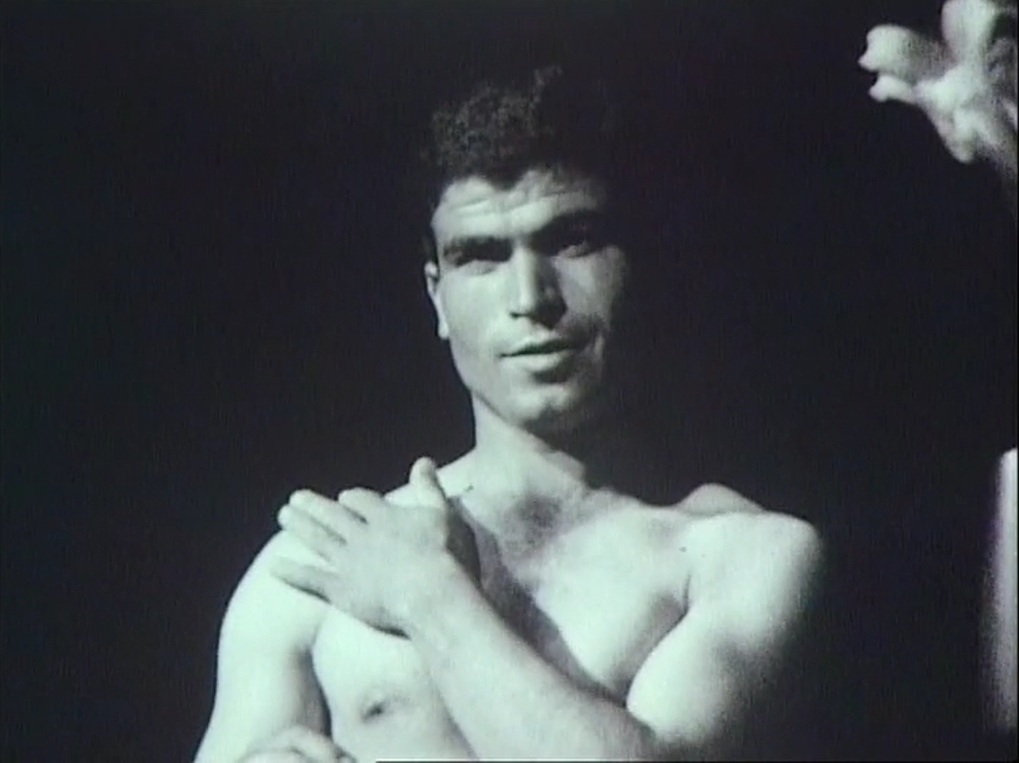

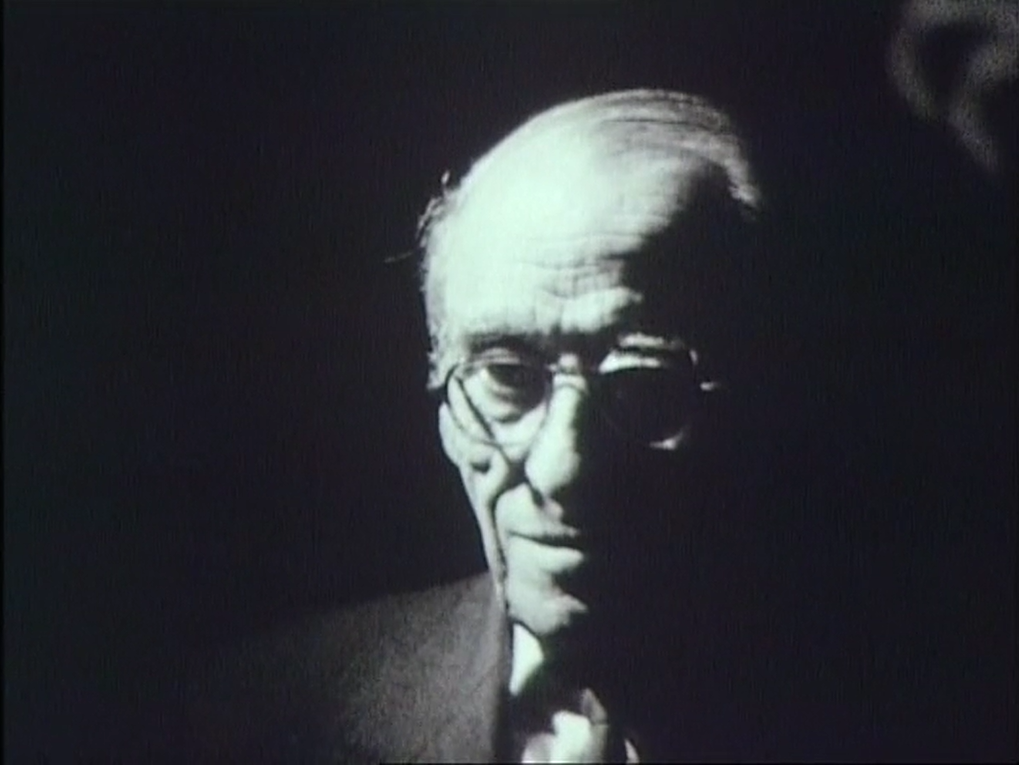

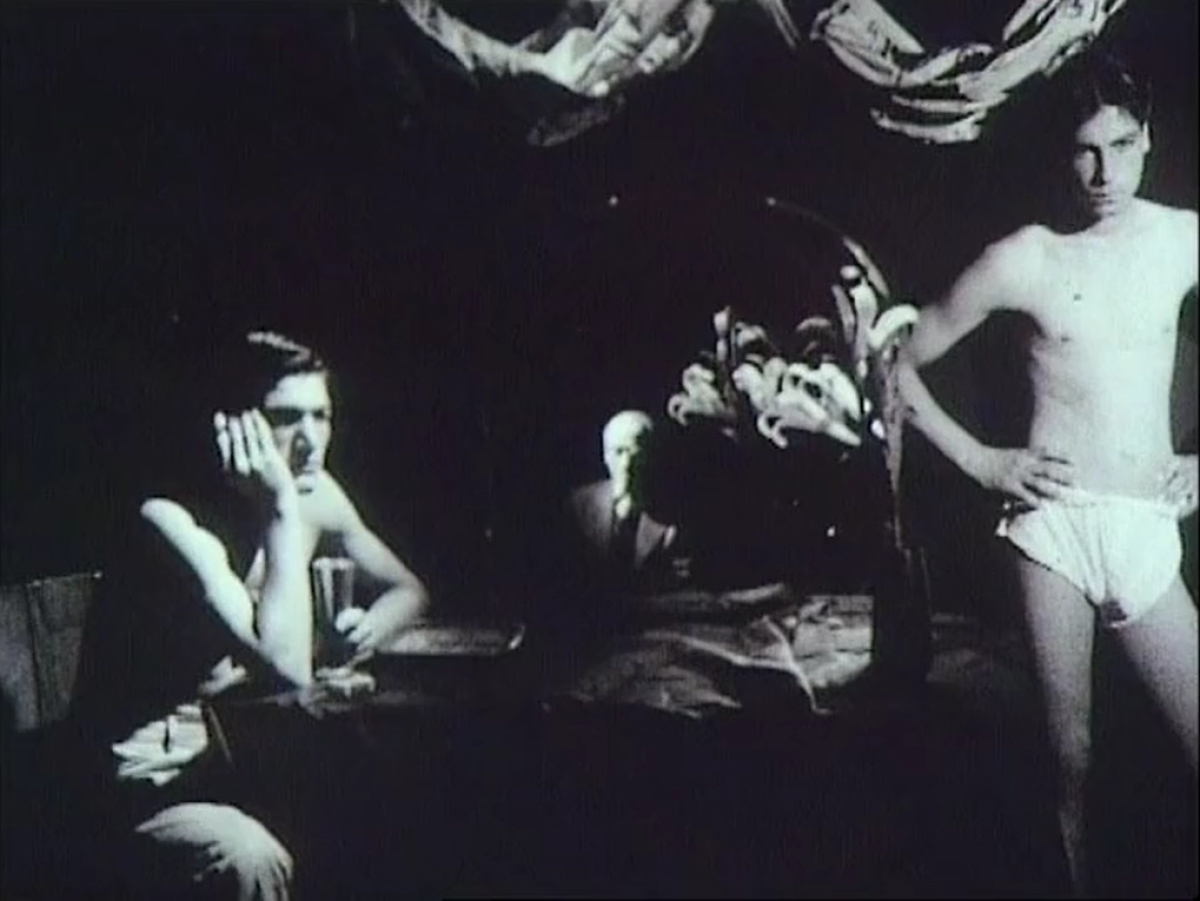

The segment I am discussing is preceded by a sequence of shots featuring Cavafy as a young man (played by Rupert Cole), burning candles, and S&M scenes, and accompanied by a voice-over reciting of the poems ‘Κεριά’/‘Candles’, ‘Επήγα’/‘I went’, and ‘Ομνύει’/‘He swears’, dedicated to the risky abandonment to ‘fateful pleasures’. Giannaris’s ingenious illustration of the poems alludes to the body burning with extreme desire but also to the bodies consumed by AIDS (Sawwas and Giannaris 2013: 138). Right after, the theme of Alexandrian young men is introduced by the following voice-over (my translation from the Greek version of the biopic): ‘His thoroughly compiled biographical notes on young men of Antiquity, today we would call them stars of B-movies, or even his historical forgeries, constituted an amazing simulation of study and objectivity, a transparent academic pretext for his desire’. The alternating shots spend time on the faces of naked young men looking directly, playfully or lustfully, at the camera (figures 2 and 3), and on Cyril Epstein, playing an older Cavafy and throwing an oblique glance (figure 4). Finally, the shot zoomed in on Epstein will open up to include two different naked men, with Cavafy in the middle (figure 5). Interestingly, while we are informed of Cavafy’s ‘thoroughly compiled notes’, we are witnessing a naked man actually writing something in his notebook, looking up and laughing at the camera (figure 2). The question that needs to be addressed is: What is he writing?

Figure 2 (all stills are from the online version of Trojans, available on Giannaris’s Vimeo account: https://vimeo.com/178348254?fbclid=IwAR0n8X3qXVgDWmu6qMzrNqU5GX3FuZQgZLW5nMamVhzYZmfVWwWHW8sEXxw. Accessed 09/10/2022)

Figure 3

Figure 4

Foucault (1994: 412-427) considered writing an exercise of thought on thinking itself conducive to training one’s self in the art of existence. For Foucault, self-writing has an ethopoietic effect in the sense that it elaborates the discourses received and recognised as true into rational principles of action. He spotlights two forms of self-writing: the hupomnemata (memory aids, or the material memory of things read, heard, or thought) and epistolary correspondence. The function of hupomnemata is not to extract a confession but, through their citational dimension, to establish a relationship of the self to the self and constitute the self as a subject of rational action by recollecting, compiling, writing down, consulting, and subjectivating fragments of things already said: meaning ‘a purposeful way of combining the traditional authority of the already said with the singularity of the truth that is affirmed therein and the particularity of the circumstances that determine its use’ (trans. in Foucault 1997: 212). Moreover, an epistolary relation entails placing oneself under the other’s gaze and bringing this gaze into congruence with the gaze that one aims at oneself. In Giannaris’s film, while we are learning about Cavafy’s method of character creation and notetaking, of ethopoesis, we see another man writing and fashioning his character. This self-stylisation by seizing and reframing pre-existing scripts is ethical not only because it casts a pensive and creative gaze on the self but also because it renders these subjects in the making visible under the eyes of other subjects in continuous self-formation. It is ethical because it involves a certain positioning towards others employing the same art of existence insofar as these hupomnemata (Cavafy’s, the young man’s, Giannaris’s) break free from their frame of intimacy and circulate, as if their very aesthetic condition was to exceed the context within which they are performing their function. In other words, this readerly and writerly practice does not simply reach towards the past in a gesture of appropriation (Giannaris towards Cavafy, Cavafy towards the Alexandrians): the very dynamics of this intellectual and affective investment are anticipating this backward movement, that future queer subject formations will be motivated by the same readerly and writerly techniques. Thus, the crafting of queer subjects is evinced as a community project, facilitated by a temporally complex ecology of metaleptic and simultaneously proleptic inroads into reading and writing that cut across each other. In considering this double haunting, from the present by the past but also from the past by the (poetics of its) future, I am inspired by and in conversation with the recent work of Dimitris Papanikolaou (2018, 2020, 2021). Papanikolaou presents this influential argument as follows: ‘we are constantly haunted not only by the past we can embrace, but also by a near-future we can construct as still to come, in multiple times, in queer failing and remaking, in plural acts and remembrances, at various moments of political exigency and queer recalling’ (2021).

Figure 5

Giannaris’s pensive shots enacted by the detail of the notepad make the protagonists stare pensively at themselves but also emerge under each other’s eyes. In the final shot, the medium shot on Cavafy opens up to unveil the two young men, standing still in the two corners, as if they were already there, both Alexandrians and contemporary, both constituted by, and constitutive of, Cavafy, all three now somehow co-present and cor-respondent. Even though their glances don’t meet, they read each other through the zig-zagged lines traced by their oblique gazes, appearing as subjects through the other’s and the spectator’s eyes, and calling us to do the same. Their common feature is that they are standing unapologetically bare, maximising their vulnerability and exposure. These bodies are pensive, readerly and writerly, and they are possible because, I argue, they have resulted from the bodies consuming and consumed we find in the ‘Candles’ segment, from bodies that, when facing precarity and risk, choose to maximise their proximity to danger.

Those ‘Dangerous Things’

Tellingly, danger is at the heart of hearts of the Cavafian enterprise. For instance, the poem ‘Τα Επικίνδυνα’/‘Dangerous’ (1911) has been underlined as a watershed moment in Cavafian poetics. Cavafy himself, in a lecture delivered by his protégé and eventual heir Aleco Singopoulo in 1918, bookmarked this particular poem as the privileged entry point for understanding his (life-)poetics. In this poem, and by putting this poem at the centre of his output, Cavafy forwards a position of ontological and epistemological insubordination grounded in a counterintuitive management of risk-taking.

By all appearances, the poem thematises a subject with conflicting allegiances, who makes repeated, protracted, and pensive pledges to himself to stick to a discipline de vie, which is pretty undisciplined, meaning finding a way to yield to his desires while at the same time managing to harness and regulate them. The poem’s main conundrum resides in pinpointing the source of danger, which is also underscored by the title’s varying translations (such as ‘Dangerous’, ‘Dangerous Things’, ‘Dangerous Thoughts’). Nevertheless, danger is utterly absent from the poem and seems only to be encircling or framing it through the paratextual element of the title. In this vein, the main body of the poem is concerned with two affects managing this circumscription within danger, that is, with the ‘absence of fear’ and with the feeling of empowerment generated by reflection, which have been perceived as a duet of affects being in competition and/or mutually exclusive: ‘“Strengthened by contemplation and study, / I will not fear my passions like a coward. / My body I will give to pleasures, / […] and I will have the will [to recover my spirit] strengthened / as I’ll be with contemplation and study […].”’

So, what is dangerous? Myrtias’s lifestyle which will attract societal reprobation (seeking ‘the most daring erotic desires’)? The backlash of society itself? Myrtias’s passions, if ‘πάθη’ is the only word in the poem that corresponds grammatically to the title? Myrtias’s delivery of a controversial argumentation or the fact that, through a dangerous reasoning, these passions can be perpetuated and are presented in constant gestation? Before answering that, we must pay heed to the fact that Myrtias is dangerous because he is already in danger. Myrtias is introduced as ‘a Syrian student in Alexandria’, as ‘partly pagan, and partly Christianized’, as living in times of political instability and experiencing ‘lustful impulses’ of blood. Motivated by Butler (2009), I am reading Myrtias’s identity markers, in all their indeterminacy, as frames, meaning ‘normative conditions for the production of subject produc[ing] an historically contingent ontology’ (4). As a result, Myrtias’s exposure to and constitution by socially and politically articulated powers, on the one hand, produces, contains, and conveys him as a recognisably precarious subject, as a national, religious, and perhaps political Other, as a precarious sexual, if not sick, and threatening alterity. On the other hand, however, our very capacity to apprehend and recognise Myrtias’s precarity depends on these norms that establish domains of the knowable.

At first sight, Myrtias’s affective reaction to this framing of his subjecthood is to control his propensity for illicit pleasures by relying on a ‘strengthening’ ascesis based on contemplation and study. As explained by Singopoulo, Myrtias’s ascetic ‘strengthening’ is afforded beforehand and maintained in the guise of a ‘[cultural and intellectual] capital’, perhaps mined directly from one of Cavafy’s unpublished poems. ‘Whoever longs to make his spirit stronger / should leave behind respect and obedience. / […] and he will leave behind / the norms that he received, inadequate’: ‘Δυνάμωσις’/‘Strengthening’ (1903) unfolds as a credo for an aesthetics of the self, crafted both by the stylising pressure exerted by already entrenched scripts and, most importantly, by a critical stance towards this process of self-formation, permitting the surfacing of an unruly, disruptive, and desubjugated self. Thus, Myrtias’s hupomnema on which he leans for his management of dangerous desires does not neutralise his tendency towards risk but exacerbates it. Myrtias does not say, as a traditional Greek reading would have it, that he will alternate between ‘passions’ and ‘contemplation’, thus purifying the former by ‘returning’ into the latter after any excess. What he says is that, through contemplation, he can give himself to desire more fully, more excessively and without fear.

Myrtias’s affective reaction to the framing of his desires is to give into them, to cede to his dangerous desires without fear, for he is finding himself not only fettered within a fearful predicament but also familiar with what risking entails both for the endangered subject and for the frames that confine it to danger. Myrtias’s desires are dangerous as, by maximising his precariousness instead of striving to minimise it, he becomes dangerous himself and casts doubt on the taken-for-granted character of frames which have inscribed him within the realm of danger in the first place. Even though the outcome of his endeavour is held in abeyance, it is exactly this suspension that brings into relief the apparatuses that taxonomise Myrtias’s lifestyle as a lost cause and proposes something completely different. Myrtias’s practices are called ‘dangerous things’ by a social framing that fears exactly the ways in which they perform: that they furnish a primer of an aesthetics of the self and of existence in which danger, in the guise of radicalised precarity, desire, and the need for social questioning intersect with and build on each other.

To conclude with the words of Amber L. Hollibaugh (2000: 260-268): ‘Our movements and our decisions were fraught with potential danger: […] I live in a world that makes wanting sex, actualizing and realizing desire, a thing of danger. To create a movement willing to live the politics of sexual danger in order to create a culture of human hope. This is my dream today. These are my most dangerous desires.’

References

Bartlett, N. (1988), Who Was That Man?: A Present for Mr. Oscar Wilde, Masks, London: Serpent’s Tail.

Bateman, B. (2017), The Modernist Art of Queer Survival, Modernist Literature and Culture, New York: Oxford University Press.

Boletsi, M. (2018), The Futurity of Things Past. Thinking Greece Beyond Crisis, Inaugural Lecture, Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam.

_____ (2022), ‘Haunted and Haunting: Reading Cavafy Preposterously’, International Cavafy Summer School 2022: ‘Cavafy Mediated’, Onassis Foundation, Athens, 13 July.

Butler, J. (2004), ‘What is Critique? An Essay on Foucault’s Virtue’, in J. Butler, S. Salih (ed.), The Judith Butler Reader, Malden, Mass., and Oxford: Blackwell, pp. 302-322.

_____ (2009), Frames of War. When is Life Grievable?, Brooklyn, NY, and London: Verso.

Cavafy, C. P. (2009), Collected Poems (translated, with introduction and commentary, by Daniel Mendelsohn), New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Foucault, M. (1994), Dits et écrits 1954-1988, vol. IV 1980-1988, Paris: Gallimard, especially texts no. 293, 311, 313, 314, 349, 358.

Foucault, M. and Rabinow, P. (ed.) (1997), Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth. The Essential Works of Michel Foucault 1954-1984, vol. 1 (translated by Robert Hurley and others), New York: The New Press.

Giannaris, C. (1990), Trojans: A Life of Constantine Cavafy, https://vimeo.com/178348254?fbclid=IwAR0n8X3qXVgDWmu6qMzrNqU5GX3FuZQgZLW5nMamVhzYZmfVWwWHW8sEXxw. Accessed 09/10/2022

Hollibaugh, A. and Allison, D. (foreword) (2000), My Dangerous Desires: A Queer Girl Dreaming Her Way Home, Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press.

Koestenbaum, W. (1994), The Queen’s Throat: Opera, Homosexuality and the Mystery of Desire, London: Penguin.

Papanikolaou, D. (2015), ‘The Pensive Spectator, the Possessive Reader and the Archive of Queer Feelings: A Reading of Constantine Giannaris’s Trojans’, Journal of Greek Media & Culture, 1:2, pp. 279–97.

_____ (2018), ‘Critically Queer and Haunted: Greek Identity, Crisiscapes and Doing Queer History in the Present’, Journal of Greek Media & Culture, 4:2, pp. 167–86.

_____ (2020), ‘Remembered for What We Are About to Do: Haunted and Haunting at a Time of Biopolitical Realism’, talk delivered within the framework of the FFT Research Seminar Series hosted by the University of Reading, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IbiRcCJTi1g&ab_channel=FTTReading, online session. Accessed 09/10/22.

_____ (2021), ‘Remaining Critically Queer; and Being Haunted’, talked delivered within the framework of Queer Epistemicides. Languages, Knowledges, Sexualities. IMLR Regional Conference, 29-30 April, https://www.queerepistemicides.com/18-dimitris-papanikolaou. Accessed 09/10/22.

Robinson, C. (2005), ‘Cavafy, Sexual Sensibility and Poetic Practice: Reading Cavafy through Mark Doty and Cathal Ò Searcaigh’, Journal of Modern Greek Studies, 23:2, pp. 261–79.

Sawwas, S. and Giannaris, C. (2013), ‘« Nos efforts sont comme ceux des Troyens ». Entretien avec le cinéaste Constantin Giannaris’, Europe, 1010–11, pp. 133–44.

Sedgwick, E. K. (1991), ‘How to Bring Your Kids Up Gay’, Social Text, 29, pp. 18-27.

_____ (1993), Tendencies, Durham: Duke University Press.

Singopoulo, A. (1918), ‘Διάλεξις περί του ποιητικού έργου του Κ.Π. Καβάφη’ (‘Talk on the poetic oeuvre of C.P. Cavafy’), in M. Pieris (ed.) (2012), Εισαγωγή στην ποίηση του Καβάφη. Επιλογή κριτικών κειμένων (Introduction to Cavafy’s poetry. A choice of texts of literary criticism), Heraklion: University Press of Crete, pp. 47-56.

Billie Mitsikakos is a DPhil researcher at the University of Oxford. Before he studied Modern Greek and Comparative Literature at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki (BA) and at the Sorbonne (MA). His research project, entitled C. P. Cavafy and the Art of Queer Survival, ventures to cast light on the affordances of the aesthetic and of cultural texts as anchors for queer survival, taking C. P. Cavafy and his queer afterlives as its primary case study.