Allegories of the Fantastic in Globalization:

The Four Levels of Medieval Allegory in Ioanna Bourazopoulou's 'The Guilt of Innocence'

08 February 2024

Panos Stathatos independent

Prompted by the rise of the genre of fantasy in recent Modern Greek literature, this paper wishes to explore the function of allegory in the novel Η ενοχή της αθωότητας [The Guilt of Innocence, 2011] by Ioanna Bourazopoulou, taken as a paradigmatic case of the complexity of the mechanism of allegory in small literatures. This reading first aims to move away from the misuses of allegory as a system of merely one-to-one similarities by demonstrating Fredric Jameson’s pluralistic revisiting of the medieval system of the four levels of allegory from a Marxist perspective. Second, it aims to make some introductory comments for a study of ideology in the work of the “Greek Ursula Le Guin”, Ioanna Bourazopoulou.

The Four Levels of Medieval Allegory

Allegory seems to be on everyone’s lips nowadays. Generally, it is called upon when a cultural text seems to contain a second, implicit meaning, hidden behind its literal meaning. When it means something other than itself, when the literal elements of the work refer to a second state of things without which the text would be incomprehensible. Hence, it is clear that allegory is linked to narrative and interpretation.

Yet, this stumbles upon what Pierre Macherey called the interpretative fallacy (Macherey 2006, 46), that is, the illusion that texts include a hidden meaning which the critic intends to reveal. Contrary to this restrictive conception of allegory, Fredric Jameson has stated in his reading of Brecht’s work that allegory constitutes a wound in the text, one that cannot be closed, and the only thing writers can do is to place controls, to limit its meanings and to reduce the range of the possible interpretations that may arise from the various subjective positions from which the given text is perceived (Jameson 1999, 153). Bourazopoulou herself disagrees with allegory as a restrictive interpretation, stressing that we are products of a variety of influences and reminding us that texts take on numerous different interpretations across the time and the space in which they are read (Bourazopoulou 2015a).

Thus, it is necessary to demonstrate the ways in which allegory could be analytically useful. This requires some methodological clarifications on Jameson’s use of the concept throughout his work, culminating in his seminal Allegory and Ideology (2019). Already in Marxism and Form (1971), Jameson would agree with Walter Benjamin that allegory becomes a symptom of the disembodiment of the world, of the power of objects over people: "allegory is precisely the dominant mode of expression of a world in which things have been for whatever reason utterly sundered from meanings, from spirit, from genuine human existence" (Jameson 1971, 71).

If that indicates the omnipresence of allegory in the way we tend to grasp reality, it is important to note where allegory stands in the dialectic of Identity and Difference. For Jameson, allegory thrives in the gaps, namely in the difference between the two narratives. Thus, he rails against the allegories of similarity, which imply a one-to-one relationship between the text and the external referent, stating that they ought to be treated as “bad allegories”, which distinguish the two parts without re-uniting them, imposing a static meaning to the respective work (Jameson 2019, 4-11). Instead, allegory is useful as a diagnostic tool for opening up the text on multiple levels, exploring the dialectical slogan that first appeared in Postmodernism: "Difference relates” (Jameson 1992, 31).

Thus, Jameson delves into the four-level system of medieval allegory (see: Jameson 1971, 60-61; Jameson 1983, 14-17; and Jameson 2019, ix-xxi, 1-48). The purpose of this system was to read the events of the Old Testament as allegories of those of the New Testament and the life of Christ, establishing four levels of analysis: the literal, that is the Old Testament understood as a retelling of historical events; the allegorical or mystical, namely the life of Christ in the New Testament; the moral, that is the fate of the soul of the Christian subject; and the anagogical, namely the collective projection of the fate of all people according to the Scriptures, in other words, the Second Coming (Jameson 1983, 15-17).

These four levels have the advantage of opening up the cultural text to successive redefinitions and rewritings, preparing it for ideological investment (Ibid, 14). Jameson utilises these levels to make an allegorical reading of the medieval allegory itself: he retains the literal level as the letter of the text; then considers the allegorical as the methodological key, the very interpretive method chosen to approach it; he links the moral to the individual subject according to psychoanalysis; and he ultimately considers the anagogical as the political, or the collective meaning of History. Jameson also underlines that the levels are characterised by a kind of Guattarian transversality (Guattari 2015, 105-120), constantly interacting without overlapping and, thus, these levels are only fruitful when both separated and united.

For Jameson, allegory as differentiation becomes again topical in the period of globalization, with its consequent homogenization of the world on a linguistic, cultural and economic level. Allegory is understood as a social symptom engaging the issue of the representation of totality or, better still, representability, as the limits of possibility of representation (Jameson 2019, 34-37). In this respect, a novel of the fantastic genre, published in "small" Modern Greek literature (Casanova 2004) in the midst of the financial crisis that hit Greece in the 2010s, will be indicative of the revival of allegory in globalisation.

Mapping Allegory in The Guilt of Innocence (2011)

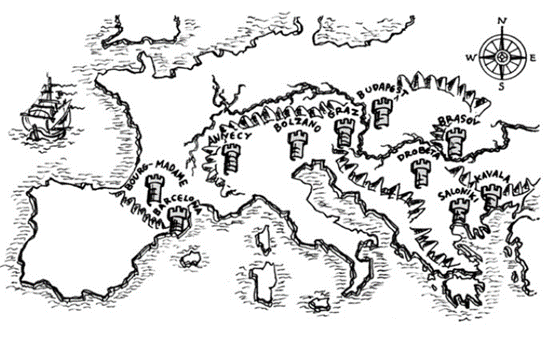

The Guilt of Innocence is set in a distant future (though it is unclear how distant it is) in Europe, where a regime called “Republica Corporativa Europae” has replaced the fictional system of post-capitalism. This political system is characterized by two major rearrangements: first, national identity has been replaced by professional identity, triggering a division into nine professional guilds, each in a distinct city in Southern Europe: Merchants, Healers, Priests, Judges, Manufacturers, Intellectuals, Positives, Artists, and Guardians. What we have here is an enclosed system reminiscent of castes, constituted by highly specialised professional communities in which only vertical mobility is allowed within castes. A career change via horizontal movement from one caste to another is impossible. The second rearrangement seems to be a radical change in the position of death in the fictional society: in the novel's most peculiar and implausible aspect, death has become superior to life itself, the first and foremost symbol of this dominant regime.

Figure 1: Map of Bourazopoulou's dystopian Europe, in Bourazopoulou (2011, 8)

Figure 1: Map of Bourazopoulou's dystopian Europe, in Bourazopoulou (2011, 8)

The plot revolves around two mismatched friends, our protagonists, Joseph Eralis, from the lower ranks of the Artists, and his fellow, nicknamed “Stork”, from the lower ranks of the Intellectuals. They are chosen to transport the so-called “Ark of Democracy” from city to city, due to a referendum concerning the death sentence of the person sitting inside this Ark, whose identity must remain unknown to the voters. The continuation or the dissolution of the regime depends on the outcome of this referendum.

Labor as an Imaginary Resolution of Contradictions

Undoubtedly, the novel's world-building with this absolute division of labor launches a fierce attack on specialisation. However, we get a sense that the literal level is already allegorical, when we look closely into the perception of the profession as the only remaining source of social identity: "The 'professionals' were endemic in Europe since the Middle Ages, but remained sociologically invisible because they were not recognized as a 'social class' or 'social stratum' or even as a distinct 'social group' [...] The status of the 'professional' replaces that of the citizen and the only social identity is the profession" (p. 27-28). However, it is a structural necessity that in order for this fictional organisation to become accessible to our imagination, professions must be transformed into characters (Anderson et al. 2019), which draw on the current social stereotypes about professional fields that constitute the raw material of representation. This is essentially an allegorical mode of representation that leads us to identify the characters with the stereotypes relating to their corresponding caste. As a result, their individuality is absorbed by the group, which becomes apparent through their vocabulary. This is demonstrated in several examples: the sturdy handy Vronka of the Manufacturers (160-162); the glass towers where the Intellectuals study uninterrupted and remote from society (187-188); the steady, colourless, “robotic” voice and the genetic purity of the Healers (272-278); lastly, the dreamlike atmosphere of Artists and Priests that blurs the boundaries between reality and fantasy or awakening and dream (293-296) which alludes to artistic and mystical experience, respectively.

Yet, beyond this anti-utopian fear of the absorption of the individual by the group, the division of the world into castes suggests an essentially utopian impulse, imaginarily resolving a major contemporary problem, that of unemployment. For Marx (1990), unemployment was a constitutive element of the capitalist mode of production, with the reserve army of the unemployed always available to feed the system with human labor in order to continue producing even after major crises that force the capitalists to fire workers. In globalised capitalism, unemployment takes a new centrality, as evidenced through the changes in the working environment forcefully brought by new technologies. Indeed, for Jameson, the Capital itself is mainly a book about unemployment (Jameson 2011, 146-151). As capitalism cannot function under conditions of full employment, a number of social problems arise from the system’s inability to satisfy the productivity of all its members. Thus the antinomies of labor is a recurring theme in several utopias (Jameson 2005, 142-159).

In any case, the inevitable reverberations of the increased levels of unemployment during the Greek financial crisis (in 2011, when the novel was published, Greece was experiencing a severe financial crisis that started in 2009) demonstrate that the conception of the castes and of professional identity are perhaps more utopian than dystopian. In other words, the caste system manages to imaginary resolve two fundamental problems with one stroke, namely the traumatic experience of national identity and unemployment.

Self-Reference and Interpretation

However, this extreme division causes new problems, and here we have to turn to the self-reference of the novel, which makes it a novel about interpretation itself. In every city they travel to, the protagonists have to face not only the stereotypes of each caste, but also the different ways in which the castes interpret the content of the Ark. While, in theory, the referendum is about the constitution of the regime in general, in practice, as the Stork observes, "the problem in this referendum is that each caste considers that the dilemma concerns exclusively itself" (283). Indeed, each caste ends up giving convincing arguments explaining why within the Ark lays one of its own representatives. This practice recalls Walter Benjamin’s view on the dominant power of the allegorists to instill their own meaning into the object at hand.

This self-referentiality is also evident in the form of the novel itself: in the Budapest chapter, which turns to the city of the Artists, the narrative takes the form of a theatrical dialogue. This unique “theatrical” chapter stands in contrast with the argumentative dimension of most of the dialogues in the entire book. It is evident that each caste becomes an Intellectual in its own right, while the extraordinary persuasiveness of each argument creates the sense that they are all somehow correct. The fact that the Ark turns out to be empty, not only demonstrates the allegorical nature of all interpretation, but also indicates the power of interpretation, as well as the life-giving interpretive potential of emptiness as such.

Death and History

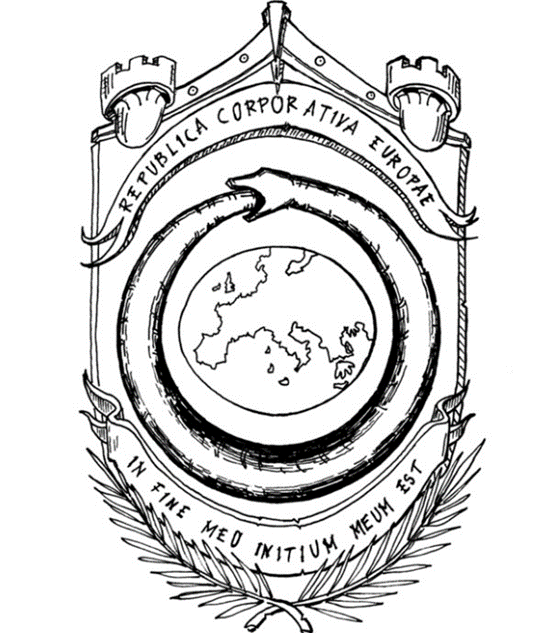

We now move to the moral level, which concerns, of course, death itself and its peculiar place in the novel. Death is about morality because in this regime it receives an existential, psychoanalytical dimension: “the right to work and the right to death [...] are the main sources of anxiety for Europeans” (146). Apparently Bourazopoulou's target is not so much death itself, as it is the Western perception of it, as stated in many interviews. The symbol associated with death is the Ouroboros serpent, the snake that eats its own tail, a popular symbol of the alchemists. Jorge Luis Borges, in his Manual de Zoologia Fantastica (1957), associates the symbol of the Ouroboros with death, citing the story of Queen Mary of Scotland who had carved into a gold ring the phrase: "In the end is my beginning" (Borges 1957). It is no coincidence that Bourazopoulou paraphrases Borges in the slogan “My end is my beginning", making it the signature motto of the regime.

As Giorgio Agamben has convincingly shown, every figurative conception of time is a comment on the philosophy of history, carrying within itself a historical worldview (Agamben, 1993: 89-105). The circle marks a static and ahistorical conception of a time that returns to itself, the seasonal time where nothing ever changes, which Castoriadis (1998) and Guy Debord (1995), among others, have denounced. Thus, the strict circular closeness of the regime condensed in the symbol of Ouroboros responds to a cancellation of historicity, which in turn allegorically responds to the loss of historical consciousness of the subjects of our current globalised society.

Figure 2: Symbol of Ouroboros, in Bourazopoulou (2011, 7)

Is There a European Collectivity?

Now, we have eventually reached the fourth level, asking the most crucial question for times like ours that seem to be stuck in an eternal capitalist present: how did we end up here? As mentioned from the beginning, the imagined Republica Corporativa emerged in Europe as a response to the collapse of an earlier system called “post-capitalism”. However, the author does not provide much information about the latter, besides only scattered hints: Europe’s crawling behind the flexible US and fast-growing Asia, the ideological decline and productive stagnation of post-capitalism (59-60), the rest of the world plagued by the sloth and corruption of this system (115) in which development has been detached from consciousness, achieving only evolution with no progress (159).

Long story short, post-capitalism beats the ideology of progress but then quickly decays and falls dead in the process. Thus, post-capitalism functions in the novel less as a discrete historical stage than as a narrative device that leaves a Barthesian effet de l'historique (Barthes 1968, 84-89). What we do have, however, is a description of the Revolution that gave birth to the new regime, a peculiar revolution of "consciousness", which clarifies the second paradoxical issue of the perception of death.

Once post-capitalism reached the deepest point of decay, a mysterious Revolution took place here, changing the terms of reality. For others it was a reflex-reaction of the market, for others the coming of historical debt, for others a biological mutation; silent and bloodless, the Revolution started and ended in the collective mind, changing the view on Death. Death became the main purpose of birth, taking the place of Life, because the Beginning was created for the End. The existential shift occurred simultaneously in the consciousness of all the inhabitants of the continent, like a forest pollinated by a gust of wind, and its impact shattered millennia of social, moral and philosophical infrastructures. In the wreckage of the past, the new age sought out its chosen people. (27).

Thus, the Revolution takes on a collective, esoteric, mystical character, occurring simultaneously and unexpectedly in the consciousness of the European subjects exclusively, reprogramming them to welcome a brand-new mode of production. An Althusserian symptomatic reading would leave us with two interrelated, indicative conclusions, one about representability and one about the question of transition.

This fictional Revolution appears to be a contradictory symptom both of our need to imagine collectivity and of our conceptual inability to represent it in the first place. For collectivity belongs to the unrepresentable categories, so that the history of its representation is the history of our failed attempts to grasp it. The novel resorts to the abstract, fragile and ideological notion of European identity. Indeed, this is a recurring theme in Bourazopoulou, whose novels are indicative of the difficulty of articulating a viable and egalitarian European project in the era of the European Union, where nation-states are folding back into member-states.

Finally, attributing the moment of transition to metaphysics appears to be a symptom of our inability to articulate a concrete plan to exit capitalism, which is also the collective necessity to imagine it. The novel is a classic dialectical case of success through failure in terms of representing collectivity and transition. Again, in Bourazopoulou’s own words: “We cannot invest in the future without realizing our current mess. Let us rediscover our values from scratch. […] If we imagine the impossible, we may even attempt it” (Bourazopoulou 2015b).

These two provisional conclusions should be regarded as case studies to be tested in the broader spectrum of Modern Greek literature of the fantastic and the so-called literature of the crisis. For now, The Guilt of Innocence, through its various imaginary resolutions constitutes a closed fictional society that alludes to the open nature of transition, a closed novel with an open ending, with the four levels of medieval allegory illustrated as follows:

ANAGOGICAL: Revolution, Transition & European Identity

MORAL: Loss of Historical Consciousness

ALLEGORICAL: Self-Reference & Interpretation

LITERAL: Division of Labor

Bourazopoulou’s Universe and the (Second) Task of Modern Greek Studies Today

It would be fair to say that out of Bourazopoulou's six novels, this is most probably her most unsuccessful, the one with the least critical attention, far from the already-classic, awarded and translated, What Lot's Wife Saw (2013), and the exceptional trilogy The Dragon of Prespa. However, I believe that every novel sets the stage for the next ones, and we can speak of a Bourazopoulou universe with many constellations. Her novels address ideology and geopolitics, she is always mixing genres, she is a versatile literary cartographer with a particular interest in painting and especially theatre. Recurring themes are national identity in troubled national territories, the positioning of small countries in unequal inter-national organizations, the fate of Europe, the question of the Balkans, eventually the commodification of everything, and the extensive power of multinational corporations. And above all, interpretation, its necessity, its certain failure as well as its inevitability.

Thus, my initial assertion that Bourazopoulou is the “Greek Ursula Le Guin” would be an understatement, not only due to the modernist lesson that every writer is unique, but also due to the historicist fact that there could be no Le Guins in small literatures. National identity is ideological in itself and Greek writers witness the uneven structure of the geopolitical and literary system through the cracks of the Balkan mountains that can only return a distorted viewpoint. Recently, at Athens’ Historical Materialism conference, in my paper on Modern Greek literature of the financial crisis (Stathatos 2023), I argued that the task of Modern Greek Studies today is to connect with other literatures of the Global South on the axis of common problems. This urgent political task in our globalised world in which our domestic problems concern every other nation as well, should not make us neglect our other relevant, yet old-fashioned role: to emphasize the need for translation, to push for the journey of our cultural texts beyond their national borders. In other words, for the insatiable thirst for World Literature. Only provided that, Ioanna Bourazopoulou can claim her place in the unequal terrain of World Literature.

[All the quotes in parenthesis are from Bourazopoulou 2011. All the translations from Greek are by the author.]

References

Agamben. G. (1993), Infancy and History: The Destruction of Experience, London & New York: Verso.

Anderson, A, & Felski, R. & Moi, T. (2019), Character: Three Inquiries in Literary Studies, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Barthes, R. (1968) “L’ Effet de réel”, Communications, No. 11, pp. 84-89.

Borges, J. (1957), Manual de zoología fantástica. Mexico D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Bourazopoulou, I. (2011) Η ενοχή της αθωότητας, Athens: Kastaniotis.

Bourazopoulou, I. (2013), What Lot’s Wife Saw, transl.: Y. Pannas, Edinburgh: Black and White Publishing Limited.

Bourazopoulou, I. (2015a), Interview “Proust and Kraken”

Bourazopoulou, I. (2015b), Interview “Left.gr”

Casanova, P. (2004), The World Republic of Letters. transl.: M. B. Debevoise, Harvard: Harvard University Press.

Castoriadis, C. (1998), The Imaginary Institution of Society. transl.: K. Blamey, Cambridge: The MIT Press. [1st ed.: 1975]

Debord, G. (1995), The Society of the Spectacle, transl.: D. Nicholson-Smith, New York: Zone Books.

Guattari, F. (2015) “Transversality” in: F. Guattari, Psychoanalysis and Transversality. Texts and Interviews 1955-1971, intr.: Gilles Deleuze, transl.: Ames Hodges, New York: Semiotext(e).

Jameson, F. (1971), Marxism and Form: Twentieth century Dialectical Theories of Literature, Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Jameson, F. (1983), The Political Unconscious: Narrative as a Socially Symbolic act, London & New York: Routledge.

Jameson, F. (1992), Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism, London & New York: Verso.

Jameson, F. (1999), Brecht and Method, London & New York: Verso.

Jameson, F. (2005), Archaeologies of the Future: The Desire Called Utopia and Other Science Fictions, London & New York: Verso.

Jameson, F (2011). Representing Capital. A Reading of Volume One, London & New York: Verso.

Jameson, F. (2019), Allegory and Ideology, London & New York: Verso.

Macherey, P. (2006) A Theory of Literary Production, transl.: Geoffrey Wall, intr.: Terry Eagleton, London & New York: Routledge [1st ed.: 1966].

Marx, K., (1990), Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, 3 vols., trans. Ben Fowkes, London: Penguin Classics. [1st ed.: 1867].

Stathatos, P. (2023), “Periodizing Modern Greek Literature of the Financial Crisis”. International conference: STATE IN/AND CRISIS: Theory and Movement in a Dangerous World, Historical Materialism Athens, Athens, Panteion University, 20-23 April 2023.

Panos Stathatos holds a BA in Greek Philology and an MA in Modern Greek Literature, both at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA). In his MA dissertation he explored the interrelations between Utopia and Allegory in Greek Science Fiction, mapping the marginalized position of Greek national literature in the world literary field. His research interests include, among others, utopia/dystopia, Marxism, genre theory, national/World Literature, film and cultural studies.

related

- Ergativity as Alternative Subjectivity in Times of Crisis: The Case of Vasilis Kekatos’ As you Sleep the World Empties

- ‘Our Intense Biopolitical Moment’: Eschatological Narratives and Counter-cultures of Resistance

- Vertiginous Life: An Anthropology of Time and the Unforeseen (in Contemporary Greece)

- VIDEO: Our Intense Biopolitical Present: COVID and Before