Recollecting History, Bodies and Looks:

the Graphic Novel 'Bandits' (Part 1) by Yorgos Goussis and Yiannis Rangos

22 March 2021

Kristina Gedgaudaitė Princeton University

Yorgos Goussis and Yannis Rangos

Bandits: Life and Death of Yannis and Thymios Dovas (Part 1) (Ληστές) Athens: Polaris publishers, 2020

Some years ago now, as an enthusiastic doctorate candidate, I embarked on a project exploring the memories of Asia Minor in contemporary Greek culture. As each research journey, it was a project that expanded my ways to think about the world in more ways than I could have ever imagined! One of the much-cherished discoveries, for me, was the medium of comics and the ample opportunities it provides to approach history. The graphic novel Aivali by Soloup and its labyrinthine mirror images reflecting on the legacies of the Greco-Turkish War was what opened my door to that world. Many more graphic novels later, as my doctoral thesis was shaping into a monograph, I decided to explore the Greek graphic novels in my next research project. What follows in this post are some of my field notes as I embark on this project.

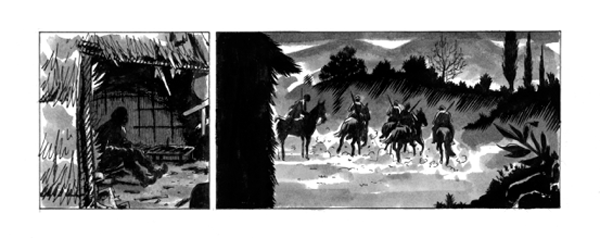

In November 2020, a parcel of books from Greece arrived at my doorstep on the other side of the Mediterranean. Among them, hot off the press, was the graphic novel Bandits: Life and Death of Yannis and Thymios Dovas by Yorgos Goussis and Yannis Rangos (Ληστές, Polaris publishers, 2020). Without much haste, I opened the book and followed the journey through its back-and-white pages, delving into the world of the mountainous Epirus at the beginning of the 20th century. In 1909, when the story of the graphic novel begins, the region of Epirus was under the Ottoman Empire, and it would not become part of Greece until the first Balkan War in 1913. Ten more years of wars followed: the second Balkan War, the First World War, the Greco-Turkish War, ending in the military debacle known in Greece as the Asia Minor Catastrophe. In this turbulent historical period, several bandit gangs flourished in rural communities, making their living by committing organized robberies, kidnapping wealthy individuals for ransom and at times also used by those in power to settle the matters when law was not on their side.

In this context, the Bandits is a story of a mountain village community, where laws promulgated through the code of honour operate parallel to the laws administered by authorities. It zooms in on the lives of the two brothers – Yannis and Thymios Dovas (characters based on the legendary bandits Yannis and Thymios Rentzos) – who stand by each other’s side no matter what: tied by blood through their descent as well as bloodshed through their crimes. It is a personal story that unfolds in the shadow of history, when Greece builds itself as a modern nation and the Ottoman Empire crumbles down. The newspaper clippings included at the end of the graphic novel attest to the authenticity of this account. At the same time, the slight name changes for the two main characters (from Rentzos to Dovas) gives the authors a license to deliberately fill in archival gaps on how life in Epirus at the dawn of the 20th century could have been.

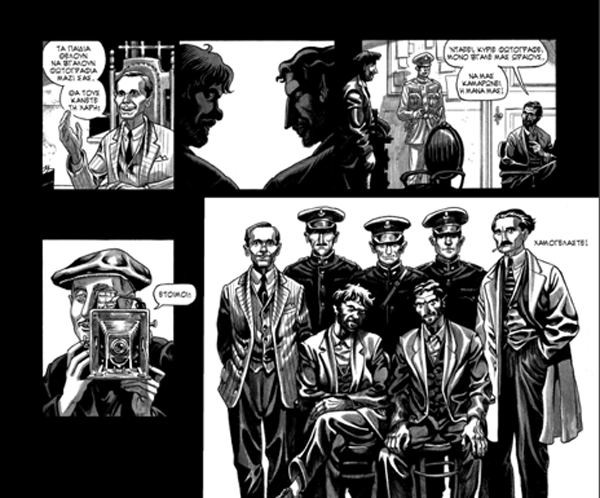

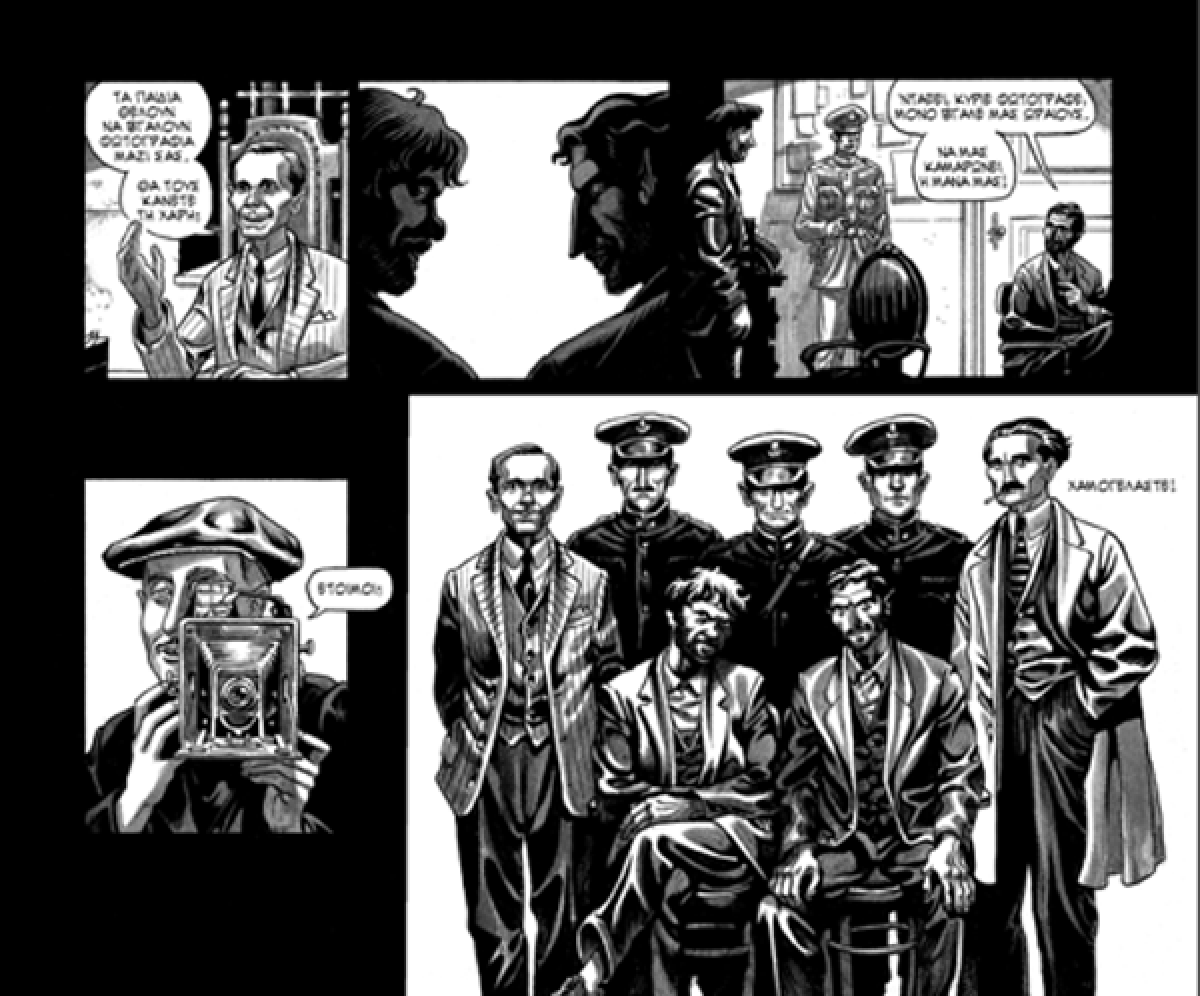

The book begins with a photograph taken in Corfu in 1930: as the two brothers are about to be executed for their crimes, several policemen crowd an office where Yannis and Thymios are taken and ask for a photograph together: “All right, Mr. Photographer, but make us beautiful, so that our mother would be proud of us!” the brothers consent and take their seats in front of the camera, surrounded by the police officers. This episode in and of itself is staged as quite a bizarre occurrence, hinting at the celebrity status that the two bandits obtained even in the eyes of those who are on the side of the law. At the same time, the photograph, sketched in the very first pages of the graphic novel, preserves something of the soon-to-be-executed bodies in an image that will most certainly make it to the newspaper title pages, yet is simultaneously intended for somebody else’s loving gaze – Yannis and Thymios’ mother. This way, the very beginning of the graphic novel links image, body, affect and history in ways that will become crucial for the entire story.

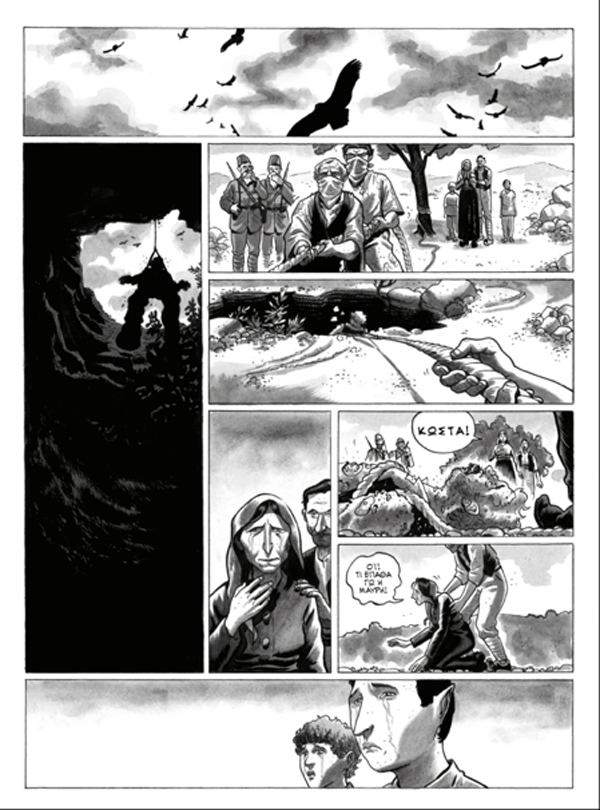

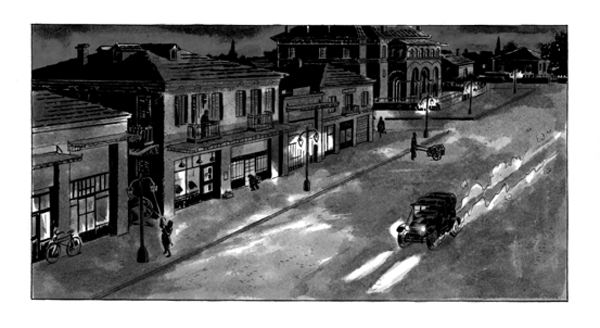

As we read through the first part of the book, entitled Roots, we uncover family and community ties that, however local, stretch beyond familiar localities, as characters navigate between mountain hide-outs and urban settlements, Greece and Albania, through safe passages known only to certain individuals. In those borderline spaces, the protagonists shift not only between localities but also languages, switching between Greek, Turkish and Albanian. We also find out the root cause for the rest of the story to unfold: the murder of Yannis and Thymios’ father and the revenge they pursue several years later, when they incidentally discover who the murderers were.

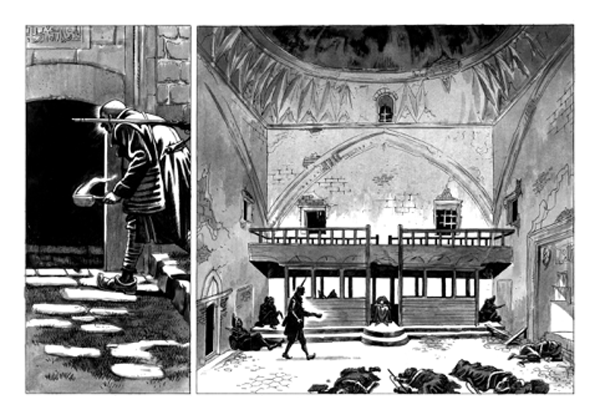

The body of the dead father and the body of his murderer are the first two that bind the brothers together as they take justice into their own hands. Drawing the readers’ attention to such bodily connections, Body, in fact, is the very title that the authors give to the second part of the graphic novel. When the brothers flee to the mountains and become the local gang’s leaders, their bonds grow closer as the number of bodies that tie their lives together grows larger - bodies of hostages, collaborators, lovers… At the same time, the graphic novel, through its drawn line, marks not only corporeality but also absences of certain bodies, when, for instance, the gang takes refuge in a mosque abandoned because the local Muslims fled the area in the aftermath of the 1923 Population Exchange between Greece and Turkey.

For the reader familiar with the Greek culture in recent years, the persistence on linking history to the body and their (un-)tangling through familial bonds cannot but remind of the dynamics that Dimitris Papanikolaou has called ‘archive trouble’, when ‘family stories are offered to us as a platform for critical and embodied reflection’ at ‘the moment when aesthetics reframes historical and political understanding and alerts us to the modalities of history in the present’. In the case of the Bandits, the boxes of the comics panels become the means to collect history in order to (re-)open it for others – the readers of the book.

The linkages that the graphic novel establishes between history, family, affect and their (re)archivization through the comics panels are the characteristics that put it in dialogue with other recent cultural works. Perhaps the most audible of these dialogues is with the close-knit communities tied by blood and code of honour that we encounter in Demosthenis Papamarkos’ Gkiak. The short story collection Gkiak recounted the experiences of men who, having served in the Balkan Wars and the Asia Minor Campaign, return to their village, struggling to rebuild their lives that are firmly bound by the strict code of honour established in their community. In the Bandits, Yannis deserts the army where he was conscripted in 1916 to avenge the murder of his father. The gun that Yannis takes with him as he flees the army determined to take justice into his own hands serves as a visual reminder that personal and collective stories always intersect, and it is at these junctures that history takes shape. The short story collection Gkiak moved its audiences by relying on two narrative devices that play an important role in the Greek cultural canon: the well-established form of the short-story and oral tradition. At the same time, it is a distinctly modern story, where boundaries between folklore and fantasy blur. The Bandits takes an episode of the Greek history that could also be considered mythologised folklore, a tale of the two bandits’ lives, and narrates it through distinctly modern genre conventions. “So much of what is going on is reminiscent of modern Westerns”, M. Hulot, chief editor of the cultural periodical LiFo, poignantly points out during an interview with Yorgos Goussis. “You are right”, Goussis agrees, “and if the first part could be considered a Western, the second part, when they move into the urban setting, could be seen as noir”. While the story of the Bandits is tapping into popular imaginary, the ways in which comics form is employed to tell this story adds another perspective.

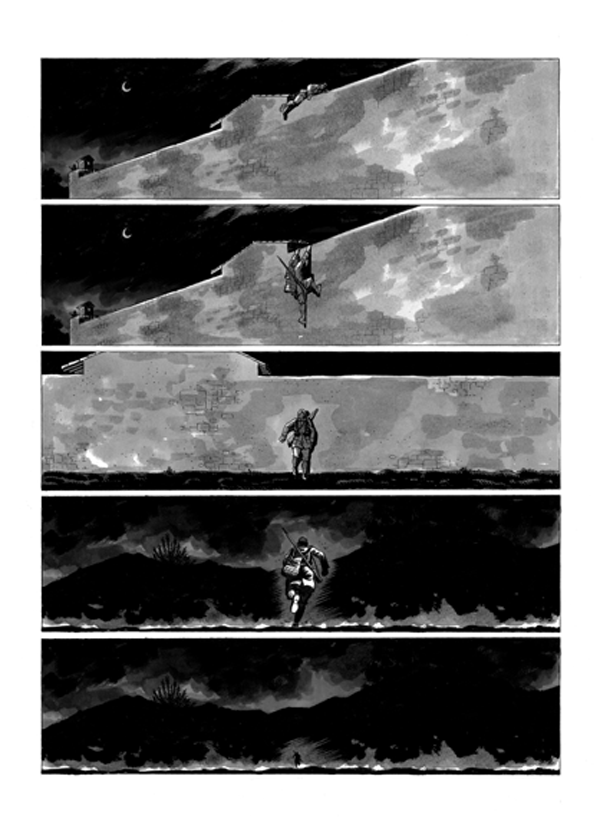

What does the comics form contribute to our reading of history in this work? Does comics aesthetics succeed in reframing the historical and the political there? The lives of the two brothers – filled with adventure and thrill – are narrated through sequences of small and medium panels that result in a fast-paced rhythm, driving the plotline forward and drawing the readers in. The fast-pace is further enhanced through a large number of scene-to-scene transitions, acting as cinematic ‘cuts’, thus cutting readers’ breath every couple of pages, as they gallop through the story along with its protagonists. As if pulling us in an opposite direction, the story is filled with affective suspense resonating through the large number of silent panels. Throughout the graphic novel, the dialogues are brief and hardly any captions are used, apart from a few lines situating us in time and place: “Corfu, 1930”, “Epirus, 1909”, Epirus, 1916”, Epirus, 1920”, back to “Corfu, 1930”... Few captions, coupled with brief dialogues and silent panels, leave the image guide readers affectively through the narrative. In those silent panels, our attention is drawn to gestures, expressions and touch; they become the central narrative devices of this story – as well as of the history that spills through it. What impact does such an affectively told history ultimately have on us as viewers? In order to see where exactly it leads us, we probably have to wait for the second part of the graphic novel to be published, which I already very much look forward to! For the moment, however, I am left with the thought that it is in those sequences of silent panels, where the power of comics to cast a look onto history can be most vividly seen. After all, among other things, comics is a vigorous exercise in looking: zooming in, zooming out, offering us close ups and panoramic views. All these looks, interchanged in the silent panels of the Bandits at sometimes dizzying pace, give us an opportunity to adjust our own angle of vision, while looking history in the eyes.

A special thanks to Yorgos Goussis and Polaris publishers for allowing to reproduce the images used for this article.

Kristina Gedgaudaitė is a Mary Seeger O’Boyle Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Seeger Center for Hellenic Studies, Princeton University. Kristina’s current project explores contemporary Greek comics and graphic novels as a site of artistic innovation and social critique and her broader research interests lie at the intersection of contemporary Greek literature and culture, migration and cultural memory.