We Need to Talk About Greece:

Why Acknowledging Racism Is The First Step To Fixing It

2 June 2021

Omaira Gill Journalist

On 24 May 2021, I was invited to be part of a very important conversation organized by Greek Studies Now: A Cultural Analysis Network and hosted by TORCH, The Oxford Research Centre for the Humanities.

Along with Rutgers University’s Sadia Abbas, Brown University’s Johanna Hanink and Generation 2.0’s founder Nikos-Deji Odubitan, I was invited to share my thoughts on the issue of ethnicity and race in Greece. The talk pivoted around a phrase we often hear in Greece: “We have never been racist”: a phrase that figured in the roundtable’s title as a provocation and thus a starting point for the discussion.

To begin to address a problem, we first have to acknowledge that it’s there, and so the first step for me is to grab this phrase and take it apart, to debunk this idea that Greeks are not racist.

Greeks have a very long history of interacting with races and cultures around the world but the fact is that it is simply not true in the lived experience of ethnic minorities in this country to say that there is no racism in Greece, or that ethnicity is not a visible aspect of life here. That’s not to say that Greece’s issue with race is among the most problematic in Europe, in my opinion it’s not. But the subject of our talk was Greece, and so it was my experience in Greece that I focused on.

Greece is an extremely uniform country in terms of race and religion. Where this becomes an issue is with the mainstream dialogue that surrounds the issue of race and ethnicity.

As ethnic minorities here can attest, if you grow up in Greece as a visible ethnic minority, even if you are born here, you still have to prove that you are more Greek than the Greeks. It’s also not uncommon for ethnic minorities who celebrate their approval of Greek citizenship with social media posts to receive abuse along the lines of trolls saying that they cannot be Greek because ‘you are born Greek, you do not become Greek.’

This hostility has historically not only been experienced by visible foreigners. It is also ethnic Greeks that have experienced this in the past as we’ve seen during refugee flows from Asia Minor, Pontus and elsewhere - even these populations, although identified as Greek by the Greek state, were categorised by their otherness and initially rejected by Greek society.

I do believe that Greeks like to think that they are not racist. This belief stems in part from a quite commonly held belief that to be racist, you have to physically attack someone. I have sat through a baffling conversation during which I brought up racism in Greece where I was challenged to list the times I had been attacked in Greece, which is zero. “Then how can you say that Greece is racist?” the other person, a Greek, asked me, resting his case that my perception of racism was all in my mind.

I’ve come across this mindset again and again, but as people who have experienced racism know it’s very often that we experience small aggressions building up over time rather than one violent episode. You don’t have to spit on someone or beat them up to be racist.

I would like to add to the conversation around race in Greece by reflecting on my own experience of how there was a shift in discourse during the years that I lived here.

I moved to Greece in 2006, before which I lived in the UK. At that time, I don’t remember feeling uncomfortable or unsafe. There were one or two instances during which I wore traditional dress while I was moving around the city for formal events or just because it is more comfortable in the Athenian summer, and I would get very intense and intrusive stares, but they did not feel hostile. I compare this to something like this: if I saw a lady on the London tube wearing a kimono, that’s unusual so I would be curious and I would look. It was harmless curiosity.

However, there was a sharp change in the atmosphere in the build-up to Golden Dawn’s rise to power in 2012. When as an ethnic minority you start to hear racist discourse become normalised in the conversations around you, even among the people you know, it’s very unsettling, but still I had the hope that it was only the venting of frustrations due to the severe economic crisis Greece was facing. We’ve seen in many countries that economic pressure makes the population look for a scapegoat, and it’s usually outsiders. Greece is not at all unique to have experienced this phenomenon of an economic crisis driving the far right to power.

But when Golden Dawn actually began to win seats, this opened a floodgate. Suddenly it was okay to express extremely racist views, it was as if people got permission to bring the worst of their feelings to the surface, even people I knew who I considered friends or family. And this is when things began to feel dangerous. This was when I, like many others in my position, began to self-censor. I felt afraid for my safety. I stopped wearing traditional clothes outside the house and I tried to keep conversations with people I didn’t know to a minimum in case I made a mistake with my Greek or my accent gave me away.

All the while, I was told that I was paranoid, but this wasn’t the case. Around us, the attacks on ethnic minorities began to escalate and very little was done. It was only when a Greek was murdered by Golden Dawn that the authorities realised that things had gone too far and tried to pull in this monster that they had allowed to grow out of control.

I recall that part of my lived experience of Greece’s history as one of the darkest for me. It is very unsettling to see the danger coming your way and to have everyone around you tell you that you’re imagining it, and to feel that if you got into trouble, the authorities you turn to for help might not help you because Golden Dawn allegedly has infiltrated the Hellenic Police.

It’s a great comfort to be here today looking at that period in time in the rear-view mirror, but still it’s an important lesson for how things like that can get out of hand in a country which famously regards itself as not racist.

For those of us who have lived in Greece long enough, becoming a Greek citizen is one of our biggest goals. Here too we face hurdles and misinformation. I have been through the process and I can tell you that it’s complex and time consuming. It is stringent in its requirements of language and knowledge of history and current affairs. Until recently it was a verbal exam, which was very open to abuse and the examiner’s own biases around race and ethnicity interfering in the applicant’s exam prospects.

Amid this, I constantly heard about how this or that government was handing out citizenship like candy to Pakistanis or whoever the unwanted ethnic minority of choice was at the time. Having been through the process from start to finish, and being the proud holder of Greek citizenship as of just over a month, I can tell you that nothing was handed to me on a plate. Meanwhile, the criteria to meet in order to apply for Greek citizenship have now gotten even more narrow in a process which was already known for being extremely selective and convoluted.

So how did we get to this point? One of the biggest problems in Greece today is who controls the narrative, and I say this as a journalist. The media in Greece is highly concentrated in a few hands, and standards, especially for broadcast journalism, are questionable. Greek news often carries segments on crimes - robberies, attacks and the rare homicide - and they make a big effort to point out the ethnicity or nationality of the accused. So you’ll hear ‘two Albanians broke into such and such place’ or ‘a Pakistani man’ or ‘a person with a foreign accent.’ It led to me avoiding saying where I was from when asked. The conversation simply carried too much negative weight when I said I was from Pakistan.

So for a while, I started saying that I was from Guyana. It’s obscure enough not to have too many questions asked, and it was liberating to not have a litany of follow-up questions about why there were so many criminals from my country of origin.

This distinction of a criminal's origins is never made when the perpetrator is Greek. What does this do? Over time, this drip feeds a narrative of foreigners, especially dark-skinned foreigners, as dangerous criminals who contribute nothing to society. What this does for the vast majority of us ethnic minorities who call Greece home is that it places an impossible burden on us. To counter this very small but very amplified group of deviants, we have to play the role of the exceptional immigrant. But let’s face it, we can’t all be Yiannis Antetokounmpo, most of us are very unremarkable, ordinary citizens living ordinary lives, working, paying our taxes, and raising our families.

How do we address this issue? We first need to acknowledge that it’s there. There are a lot of surveys and pieces of research which illustrate that Greeks are not as accepting of outsiders as they would like to think they are.

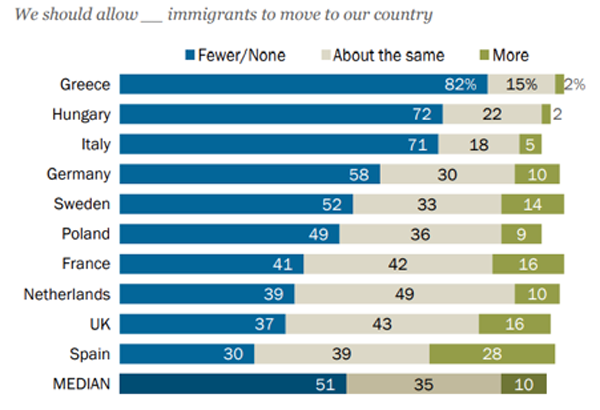

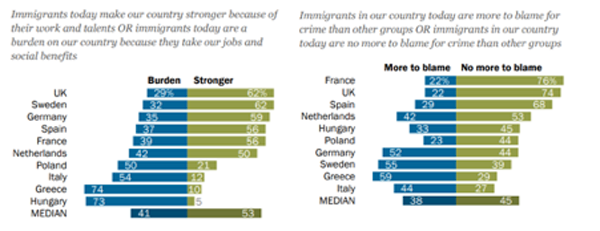

In 2019, the Pew Research Centre found that Greeks were least likely of all countries surveyed to say that immigration should increase or stay the same, with 82 percent feeling that fewer or no immigrants should be allowed into the country.

Second only to Hungary, Greeks also felt that immigrants burdened their country rather than made it stronger. Fifty nine percent of Greeks also felt that immigrants are more to blame for crime in their country than other groups, the highest of all surveyed countries.

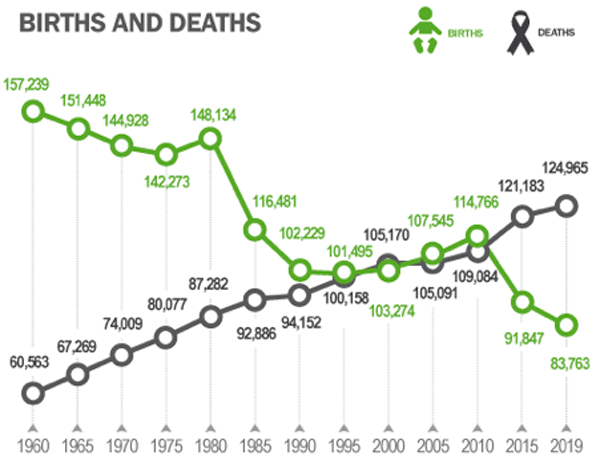

Greece is also facing a very serious demographic issue. In 2019, data from ELSTAT showed that there were 83,763 live births versus 124,965 deaths. This meant that there were 41,202 more deaths than births, the highest gap recorded so far.

Apart from boosting the birth rate of the native population, which will be slow to yield results, Greece needs immigrants to survive, keep the economy running, and pay the pensions of a rapidly aging population. If this situation isn’t remedied, projections show that Greece’s population could more than halve by 2100.

But turning to the solution of immigration to fix Greece’s dismal demographics should not mean only white immigrants. Greece’s future depends on being able to accept a non-white population into its ranks as equals who are welcome here, rather than constantly placing barriers in our way and asking us to repeatedly pledge our allegiance in a way that native white Greeks are not asked to do. This would also counter the right-wing narrative of the slow erasure of the white population in Greece by immigrants - the aim of an immigrant is not to erase but to add to growth, both in economic and societal terms.

There is a duality here at the same time, because even though Greekness is seen as whiteness and Europeanness, survey after survey shows that Greeks don’t like being told what to do by the European Union. The EU carries its own undertones of colonialism and the narrative of the white master resented by his subjects, while at the same time Greeks see themselves as white in certain contexts. Is this an overreaction to the paranoia of being one of Europe’s easternmost outposts? Is it an attempt to shake off all the years of Ottoman occupation, during which and immediately after which European visitors described Greeks as more Eastern than European, e.g. sitting cross-legged on the floor rather than on chairs? It’s an interesting paradox that needs further examining because the whiteness by which Greeks perceive themselves is pronounced when compared to migrants, but dulled when contrasted to northern European or Anglo-Saxon populations - Greeks would bristle against the idea of belonging to the same ethnicity there, and would rather identify as Mediterranean or simply ‘Greek’.

It may seem that there is a lot to be pessimistic about, but I don’t feel that way. I’m starting to see more difficult conversations around me, including initiatives such as this one, and these conversations can only lead to positive change.

It is always hard to accept that a problem exists. The natural reaction is to reject that there is something wrong with the country that you are proud of, or to be told that it’s worse elsewhere and that if I have such a problem with racism in Greece, I can leave. Greece is home for me. It’s the country I have had three children in and which I plan to live out my days in. When you love a country, it’s your duty to work to make it better and better, rather than brush its blemishes under the carpet, even if that conversation is a difficult one to have.

But if Greece can acknowledge that there is a problem, it will be the first and very important step to fixing it and creating an atmosphere where everyone in Greece can not only survive, but can also be welcomed and thrive.

Omaira Gill is a journalist and mother, living permanently in Athens, Greece. Stories published in the Guardian, DW.com, The National, UAE and more.