Greek Literature and Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

12 February 2023

Panayiotis Xenophontos University of Oxford

In Memory of Peter Mackridge (1946-2022)

Russia’s most recent, brutal invasion of Ukraine, which began on 24 February 2022, has led to thousands of civilian deaths, to say nothing of soldier casualties. In Ukraine, over 13 million people have been displaced: about 5.9 million have moved from their homes within the country, while approximately 7.8 million have gone abroad to Poland, Romania, Germany, and other nearby European countries; another, unknown amount of Ukrainians have been sent to Russia.

As a result of these horrific events, writers, scholars, and readers of Russian literature have been forced to look at their books through a more self-reflexive lens: is there something in Russian culture that has facilitated this present-day invasion and violence? If so, should we reread and reappraise the Russian literary canon more critically? Should we be more sensitive to potentially pro-nationalist and pro-imperialist themes, narratives, and discourses in the works of such sacred writers as Alexander Pushkin, Nikolai Gogol, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Mikhail Bulgakov and Joseph Brodsky? More controversially, should we continue teaching Russian literature at all? If so, how? Others have asked whether we should now concentrate our gaze on literatures in languages from the so-called peripheries of the ex-Soviet Empire.

From heated discussions on these topics over the past ten months, one can distil two main stances. The first states that Russian literature, from the Russian Empire of the eighteenth century to the present day is, for a number of reasons, a product and reflection of Russian and/or Soviet imperial ideology. Therefore, by reading and promoting this literature, you justify the current acts of aggression perpetrated by the current Russian state and its soldiers. Thus, one should stop paying attention to this literature and focus on works written by those being oppressed, in the language of the oppressed; in other words, it is imperative that we turn to Ukrainian-language writing.

The second argument states that canonical writers in the Russian literary tradition have always fought fiercely against forms of violence and totalitarianism. A writer such as Osip Mandelshtam, who defiantly composed anti-Soviet and anti-Stalinist poetry, who was arrested and subsequently died in a labour transit camp in 1938, would in no way have agreed with the foreign policy of the current head of the Russian Federation and his cronies. In addition, many Ukrainians are Russian speakers. The Russian language used by the Russian state, this argument declares, is also the one being used for totally opposite ends by those being attacked. If you stop reading all Russian-language literature, then you stop reading the stories of victims of terror who expressed, and still express, themselves in this tongue.

The opposition between these two points of view can be challenged by contemplating the position of non-Ukrainian-language and non-Russian-language literatures and literary cultures. An exploration of the case of a particular linguistic community in Ukraine, in this case the Greeks of Mariupol, complicates issues of ethnicity, nationhood, and belonging referenced in both arguments.

The Greeks of Mariupol

For over 250 years, the city of Mariupol has been home to a vibrant Greek and Greek-speaking community. The city was founded by Catherine the Great after the Russian Empire gained lands on the northern coast of the Black Sea from the Ottomans in the war of 1768–74. The first settlers of the new town and its surrounding villages were Orthodox Greeks whom Catherine had moved from Crimea. In the area, two versions of Greek have traditionally been spoken: Demotic Greek and Mariupol Greek (also known as Romeika), a Greek dialect. From the turn of the eighteenth century onwards, Turkic-speaking ethnic Greeks, who spoke Urum, also inhabited the region.

The late 1920s and early 1930s saw a sharp growth in the number of Greek and Greek-speaking intellectuals in the area; newspapers and literary journals in both Demotic Greek and Mariupol Greek started to crop up in the city in the early 1930s. There was also a Greek printing press in Mariupol at the time which published Greek language primers and translations of Russian fiction.

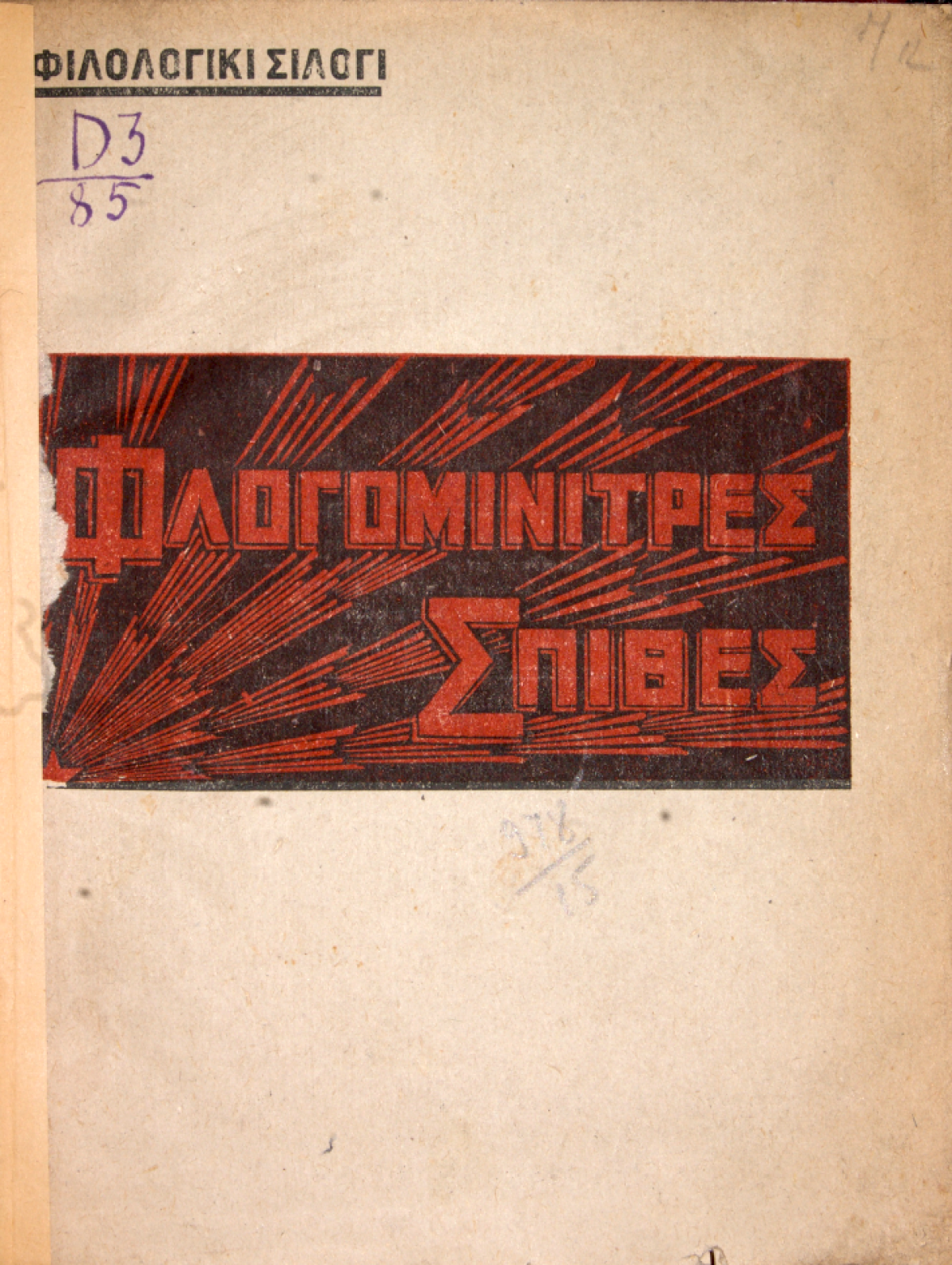

One piece of writing to appear in print in the city, in 1933, was a poetry collection, written in Demotic Greek, called Flogominitres spithes (Sparks that Foretell Flames). The anthology is predominantly made up of pro-Communist, pro-Stalinist writings; many Greek intellectuals working in the city stood behind the Soviet regime. One poem from the collection is called ‘Do you hear the storm? It’s becoming wilder, it’s groaning!’ and it discusses the future uprising of workers who currently live in a state of slavery in the western world, in contrast to the free in the Soviet Union.

The leading writer in Mariupol of the time was the poet Georgis Kostoprav (1903-1938). Despite the fact that the poets published in the 1933 collection, and Kostoprav himself, were ardent Communists, many of them were shot in 1937–38 during the Greek Operation ordered by Josef Stalin and his regime, a campaign initiated to root out supposedly subversive, anti-Soviet sentiment in the empire. In Soviet Ukraine alone several thousand Greeks were killed between 1937–38; Mariupol and its inhabitants also suffered greatly during German occupation from 1941–43. There was a mini-revival in Greek letters in Mariupol in the 1960s–1980s when extensive fieldwork was carried out in the area by Soviet scholars, but the literary culture of the city would never again reach the heights of the 1930s.

The Greeks of Mariupol and debates about Ukrainian and Russian literatures

Recent calls for renewed, more sensitive studies of Russian-language and Ukrainian-language literature can sometimes lead to oversimplifications. By looking at Greek-language literature from Ukraine – both in Demotic and Mariupol Greek – we have to readdress questions about classification: should the aforementioned literature of the 1930s, and its authors, be thought of as Ukrainian, Soviet (and, potentially, by extension, Russian) or Greek? And what about works written by Urum-speaking ethnic Greeks? If definitions of Ukrainian and Russian literature are language-based – in other words, if we say that Ukrainian and Russian literatures are those written in Ukrainian and Russian – then we risk simplifying the literary and cultural dimensions of questions raised at the start of this piece. The case study of Greek literature in Ukraine, sketched out so very briefly above, opens up questions we can ask of other ethnic and linguistic communities in the region, and thus helps further trouble current debates about Russian and Ukrainian literatures.

In a recent article in The Oxford Polyglot, written after Russia’s invasion of 24 February 2022, the late Peter Mackridge gives an overview of the Greeks of Mariupol and discusses their languages and communities. Peter ends the article on a sombre note:

"Mariupol Greek is just one of the components that go to make up the incredibly rich linguistic ecology of the lands formerly occupied by the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union. The destruction of its geographical base will inevitably lead to the imminent death of Mariupol Greek."

This death can be avoided, or at least partly avoided, through the works of individuals studying and supporting the linguistic and cultural communities of the currently decimated city of Mariupol.

Panayiotis Xenophontos is a Lecturer in Russian at the University of Oxford. He holds a DPhil in Modern Languages (Russian) from the University of Oxford. Panayiotis teaches and researches Russian-language literature from the 19th century to the present day. In addition, he is interested in the intersections between Greek- and Russian-language cultures of the 20th and 21st centuries. He is currently working on his first monograph, with the current title: Joseph Brodsky and the Visual Arts.