En croisière

23 June 2021

Dimitris Plantzos National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

In her 1971 hit Akropolis adieu, French chanteuse Mireille Mathieu relates the sad, yet inevitable, departure of a young man from Athens and his melancholic farewell to the cardinal monument of the city (“Acropolis adieu, I would have liked very much to stay, Acropolis adieu, I must now leave”). Written in German by Christian Bruhn and Georg Buschor, the song was also reincarnated in French (Acropolis adieu), English (Goodbye my love), and Spanish (Acrópolis adios). In it, Greece is depicted as an exotic paradise for melancholic summer-lovers who must part from one another when September comes. But who is the boy’s lover in the song? Who asks him if and when will he be back? To whom is he answering, “Maybe never again”? Although the questions are posed by a female, he seems to be replying only to the Acropolis itself, perhaps also gendered female here. Is the Acropolis the young traveller’s summer-lover posing the insisting questions, or does he see his real girlfriend as a personification of the Acropolis? In any case, within the song’s happy-go-lucky universe this does not make much difference: “come, let’s dance, let us forget any worries”; this is the answer to the end-of-summer tristesse – Acropolis can wait.

Can it, though? The song’s French version contains no questions, though the same melancholy may be discerned (“Et le bonheur est éphémère”, and so on). Here, again, the boy seems to be bidding farewell to the Acropolis, though a girl may be lurking between the lines. In every version of the song, therefore, Greece is constructed as a world apart, somewhat eccentric though regrettably backward, a place to visit yet certainly also a place to leave behind; a landscape of ancient glories and modern distractions from modernity itself, a land defined by its own separateness, its quasi-feminine penetrability, its supine malleability: On s'est aimés quelques jours; Acropolis adieu!

In the half century since the song was written, Greece found itself in and out of political and economic crises, national and international highs and lows, near-defeats and almost-triumphs. Only one thing remained stable: the Greeks’ resolution to achieve global recognition on the basis of their phantasmic classical heritage and the sheer fun only a Greek summer can offer. As another 1970s song claimed – this one a Greek hit, and Greece’s first ever Eurovision Song entry – all Greeks need is “a little bit of wine, a little bit of sea, and [their] boyfriend!

By the time of the 2020 pandemic, Greece seems to have decided to retain its role as the world’s designated summer resort – a sort of Donna Sheridan in Airbnb-Land. On a hot August morning in 2019, 18,000 visitors, most of them cruise passengers, visited the Acropolis, Athens’ “Sacred Rock” – an all-time record, only marginally beating the previous day’s 17,000. The Greek Minister for Culture was quoted at the time promising some action “once the summer was over”. During the pandemic, the government tried to refurbish the “Rock”, providing it with a new, expanded, cement platform on which to accommodate (slightly) larger crowds. A new plan to improve the site’s entrance capacity was also announced; both decisions were met with international discontentment, as neither step seemed particularly well designed, officially approved through the appropriate channels, or even really necessary. For while most of the Greeks – including a heavy fraction of the country’s nationalists – kept seeing Greece’s monuments as the nation’s cultural treasures, it seems that their government had decided to monetize them in ways more aggressive than before.

You see, in the land of endless summertime-loving among the classical ruins, summer is never really “over”, and the Acropolis cannot, in fact, wait. Cruise tourism had a massive impact on the global economy up to the pandemic, and the Eastern Mediterranean, including Greece, benefitted greatly from a steady growth in both annual cruise capacity and per capita expenditure. On the other hand, if the pandemic taught us anything, it was that no economy can prosper based on a single industry (in Greece’s case tourism), however vibrant it might look for a moment. Yet, the Greek government seems determined to fulfil Greece’s stereotypically orientalist imagery from the 1960s and the 1970s, as well as succumb to the pressure for continuous growth – in tourism or in anything else –, despite persistent efforts in many parts of the world, at de-touristification and global-travel degrowth. It is no accident that Kostas Bakoyannis, the Mayor of Athens, was in July 2020 dreaming of a series of thematic “market clusters” strategically implanted across the capital (from a fashion-oriented park in Kolonaki to souvenir shops in Plaka and food & beverage establishments in Monastiraki; how original is that?), riding the wave of global gentrification. If covid19 hadn’t happened, the centre of Athens might have already been turned into a brand-new thematic park exclusive to tourists and cruise passengers.

Woke me up before you go go

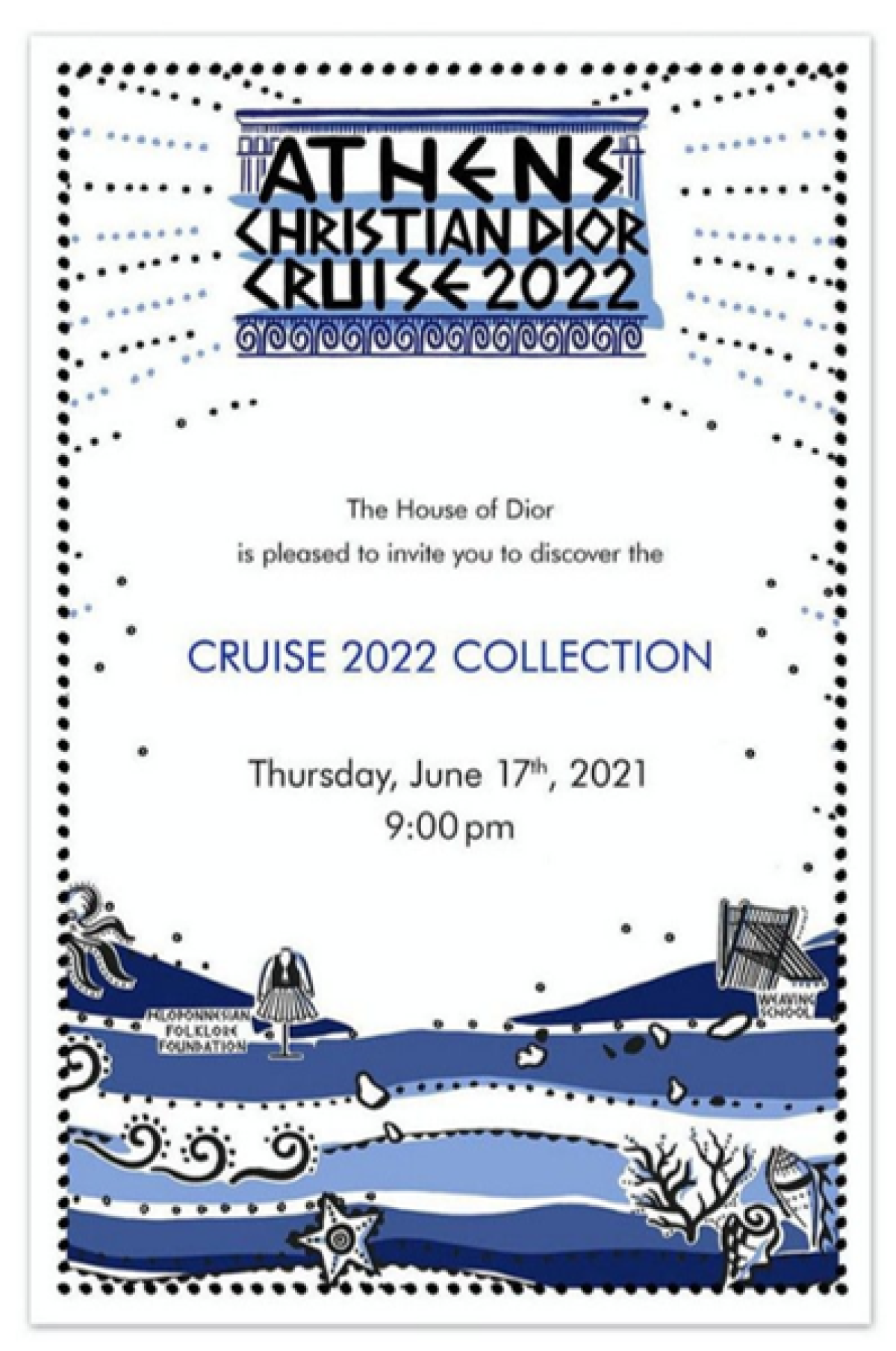

Have you ever been on a cruise? Great, isn’t it? Sailing effortlessly from harbour to harbour, sipping margueritas on the deck, wondering why on earth you are having a “Mexican night” off the coast of Crete, five o’clock in the afternoon. Still, a splendid time is to be had by all 8,000 passengers on board – provided you don’t mind the dodgy taste choices and crazy-long lines at dinner time. Cruises are even better, of course, if you are a sucker for cultural stereotypes – as in pasta and funny gesturing in Italy; curry, yoga, and sarongs in India; leis and lūʻaus in Hawaii; classical ruins and breaking plates in Greece. And it seems that this is what the designers of Christian Dior’s “Cruise 2022 Collection” poster had in mind; aimed at advertising the launching of their 2022 collection, the artwork made a significant effort at redefining kitsch through patchy pastiche: written in the by now utterly discredited “Greek” font typical of seaside tavernas in the 1970s and the 1980s, and combining an indigo-blue semblance of an islandic seabed with references to folklore costumes and … weaving, the poster manages to appear so unremarkable as to become significant. Same goes for the show’s banner – same script and style, only here Athens appears to be the sum of its sites, from the Parthenon and the Erechtheion to the Agora and a token museum. For this, in fact, is “meta-kitsch”: born at the point where even the very critique of garbage as garbage becomes trivialized, and critics appear redundant themselves. For what is there to say about a non-thing, ostensibly reviving a peripheral country’s folkloric past, a past nobody liked even when it happened in the first place?

The “launching” of the Christian Dior 2022 Collection was a 30-minute long affair taking place at Athens’ Panathenaic Stadium – rebuilt after a classical predecessor for the first Modern Olympics of 1896 – where, apparently, a hoard of 400 international celebrities were subjected to fifty shades of atrocious. If the show’s poster came from a taverna in Plaka where it would serve as paper-tablecloth to Greece’s precious guests savouring dolmathakia and kalamarakia tiganita, the catwalk itself was like the night of the living dead, only with fireworks. OK, you guessed it, fashion is not my thing and I have recently come to detest fireworks; or any party, really, where I am not invited. Lisa Armstrong, on the other hand, from The Telegraph, who apparently was invited, had a different opinion: “Dior’s new show made fashion woke”, she professed. Oh dear. Here we go again. By “woke”, I’m guessing, we mean throwing fabrics together in a seemingly effortless toga-party fashion, plastering the occasional “Greek-vase” caricature on them, and of course parading our creations through a half-lit neoclassical stadium, asking our models to appear as outlandish and bleak as their dresses. But this is hardly the point (or is it?).

Dior’s “Cruise 2022” was supposed to pay homage to a famous photo opportunity on the Acropolis from the early 1950s. Looking back at the old pictures, one cannot but marvel at the innocence of the whole affair: a crew of Magnanis, Lorens, and one or two Grace Kellies, stand sunstruck on the “Rock”, as if beamed down in their evening gowns from the big cruise ship up in the sky (perhaps this is what the Telegraph correspondent means by “woke” when she talks of the new dresses compared to the 1950s lot). The classical ruins once again play the role of the scenery: silent and inert, dusty and lonely, receiving their guests in order to see them leave again when September comes. They are revived as far (and as long as) they help their guests revive themselves. Acropolis adieu – in any language you may sing it, the resonance is always the same: one of company parted after all due services have been rendered.

The Dior show came only four years after Greece had turned down a similar request, this one by Gucci, to stage some sort of a catwalk presentation on the Acropolis itself. That proposition had been considered inappropriate and offensive, unbecoming to the “holiness” of Greece’s most venerated “Rock”, and was turned down in summarily fashion. Back then, the usual chorus of the country’s modernizers had vehemently disapproved: beggars can’t be choosers, they reminded us all, given that Greece was in the throws of yet another financial crisis. Yet, the event never happened, Gucci took their fashion and compensation moneys to Italy, and the “Sacred Rock” remained untarnished. Now, with a new government and a global health crisis still in motion, the tables have been turned, and the Acropolis gets Christian-Diored once again. Besides the catwalk show at the Stadium, photoshoots were greenlighted for several archaeological sites, and of course the Acropolis itself (according to some protesters, new sites were later added to the list, without further consultation with the authorities – when the money keeps rolling in you don't ask how, right?).

Trivializing one’s brand risks one’s financial ruin; everybody knows that. No matter what many Greeks believe, the “Rock” is not really sacred, nor does it lie above and beyond the bare necessities of life. Yet, now that Dior had their way with it, chances are that no fashion house of any repute will be asking us for our sloppy seconds. There is of course the perk of international exposure; here, however, I do believe it was fashion that benefitted from the glory that was Greece and not vice versa.

If Greece wants to resolve this post-colonial conundrum, we need to come up with a policy that makes sense: no matter how tasteless it may look to most, the Dior catwalk show was nothing more than that – a business deal. Things turn bittersweet only when the locals act as natives: as with Greece’s President, the Minister for Culture and other dignitaries who felt obligated to attend the show, even making the heartbreaking effort to appear fashionably dressed next to the Catrine Deneuves of the international show-biz world. It is then we are reliving the melancholic ending of Akropolis Adieu: when the white roses of Athens fade away, it’s time to say goodbye (till the next croisière comes along).

And then, there’s the exceptionalist fallacy: in an interview for Blue Magazine (the inflight periodical edition for Aegean Airlines), Manolis Korres, internationally renowned for being in charge of the Acropolis restorations, claimed that the Acropolis monuments and the Parthenon in particular “contain the element of eternity” and that their sight “wakes you up”, contrary to the Great Pyramid of Giza, for example, which is also eternal, yet exercises a certain “hypnotic feeling” on you (p. 220). Perhaps this is why the cement platform he designed for the Acropolis cuts off the individual buildings from their archaeological context so harshly and photo-opportunity like, turning them into holograms of themselves. Orientalizing the subaltern other – like Korres does with Egyptian culture – is a well-tried strategy of the colonists, like self-colonization remains the best survival technique of the subordinate colonial subject. At an age when the world’s top fashion houses advertise their merchandise in the manner we have come to expect from rundown tavernas on Naxos, claiming your brand is priceless might have the same cheapening effect – no one wants to buy it in the end. And the ship is already sailing.

Dimitris Plantzos is Professor of Classical Archaeology at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. He writes on classical art and its modern receptions, archaeological theory, and the uses of antiquity in contemporary political discourse. He is the author of Greek Art and Archaeology and The Art of Painting in Ancient Greece, both published by Kapon Editions in Athens, Greece and Lockwood Press in Atlanta, Georgia in 2016 and 2018 respectively, and The Archaeologies of the Classical. Revising the Empirical Canon (2014) and The Recent Future. Classical Antiquity as a Biopolitical Tool (2016), by Eikostos Protos and Nefeli Editions respectively (both in Greek).