Dear Documenta, 5 Years On:

A Conversation with Eirene Efstathiou

10 May 2022

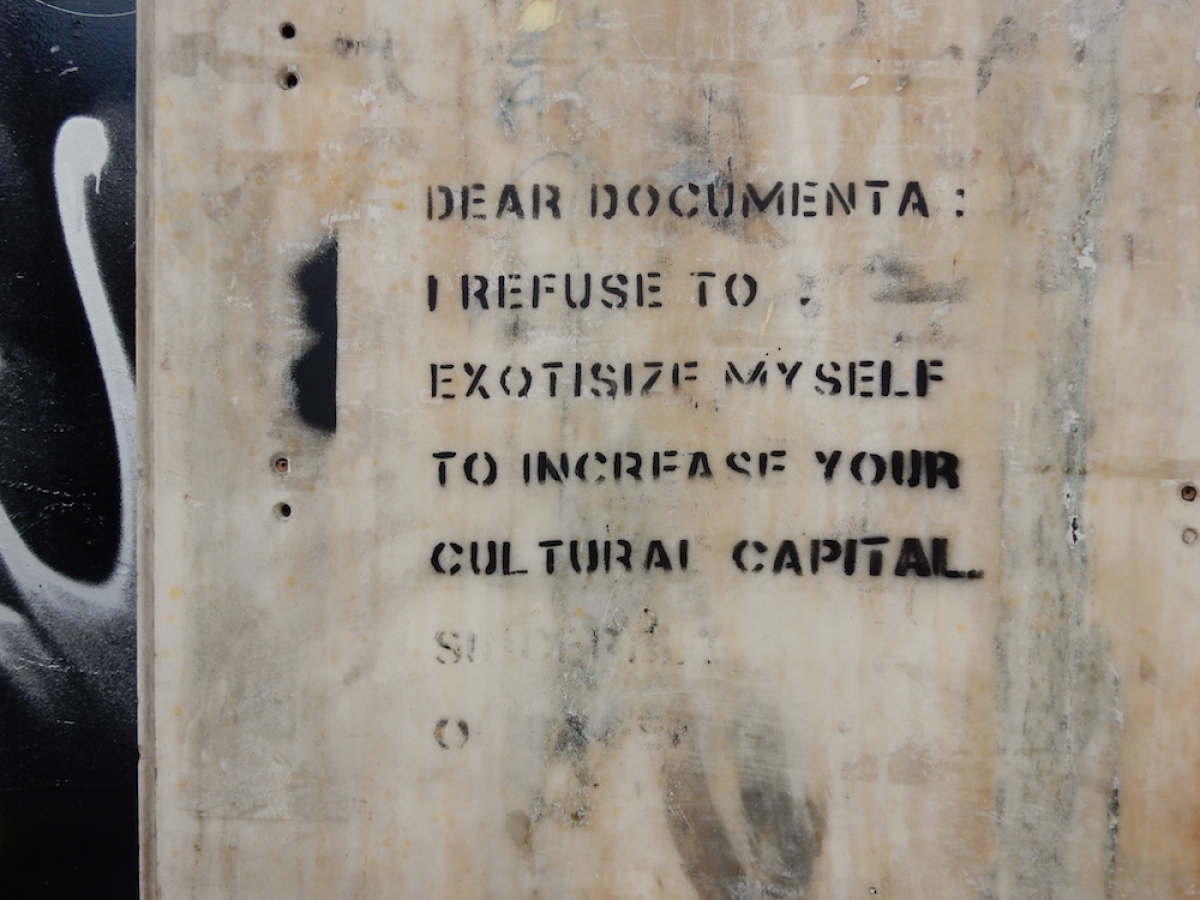

Julia Tulke University of Rochester, Eirene Efstathiou Visual Artist

Having studied and archived political street art and graffiti in Athens since 2013, a large measure of my time spent in the city over the years has been dedicated to psychogeographic photo walks. In the summer of 2016, during one such outing, I happened upon a small stencil affixed to a doorway in Omonoia Square. Comprising five lines of simple black text, it defiantly asserted “Dear documenta: I refuse to exoticize myself to increase your cultural capital” (fig. 1)—an early index of the contentious relationship between the creative landscape of Athens and the institutionalized contemporary art world, slated to descend upon the city for the 2017 installment of the prestigious German art exhibition, organized around the programmatic proposition Learning from Athens. I soon learned that the work originally included the enigmatic attribution, “Sincerely, Οι ι8αγενείς [the indigenous],” which had been selectively erased by the time of my encounter. The following year, with documenta underway and anti-documenta interventions proliferating in the streets of Athens, I located two more stencils adorned with the same signature, yet, despite my best efforts, was never able to ascertain who was behind the series.

In June 2021, five years after my initial encounter with the project, I found myself on the rooftop of the Athenian Goethe Institute attending the inaugural event of #Instituting, an experimental research program on self-organization co-curated by Gigi Argyropoulou and Kostas Tzimoulis for HKW’s New Alphabet School. At the conclusion of the evening, which had featured ruangrupa, the Indonesian artist collective appointed with the artistic direction of the forthcoming installment of documenta, I struck up a conversation with visual artist Eirene Efstathiou. Discussing our mutual interest in the Athenian urban political ecology, she casually presented me with a photograph of a stencil piece she had made for an exhibition tied to the program; red spray paint on a beige canvas bag, it read: “My hometown went to documenta 14 and all she got me was this crappy immaterial legacy, Οι ι8αγενείς” (fig. 2). It was the kind of unexpected revelation that sends a scholar of anonymous interventions soaring with exhilaration.

Figure 2. Installation view of “My hometown went to documenta 14…” tote bag at the group exhibition “Systems, Organisms, Symbiosis” at the artist-run space OXTO/EIGHT,

curated by Gigi Argyropoulou & Kostas Tzimoulis as part of #Instituting. The exhibition label reads “Anonymous, 2017.” Photograph by Julia Tulke.

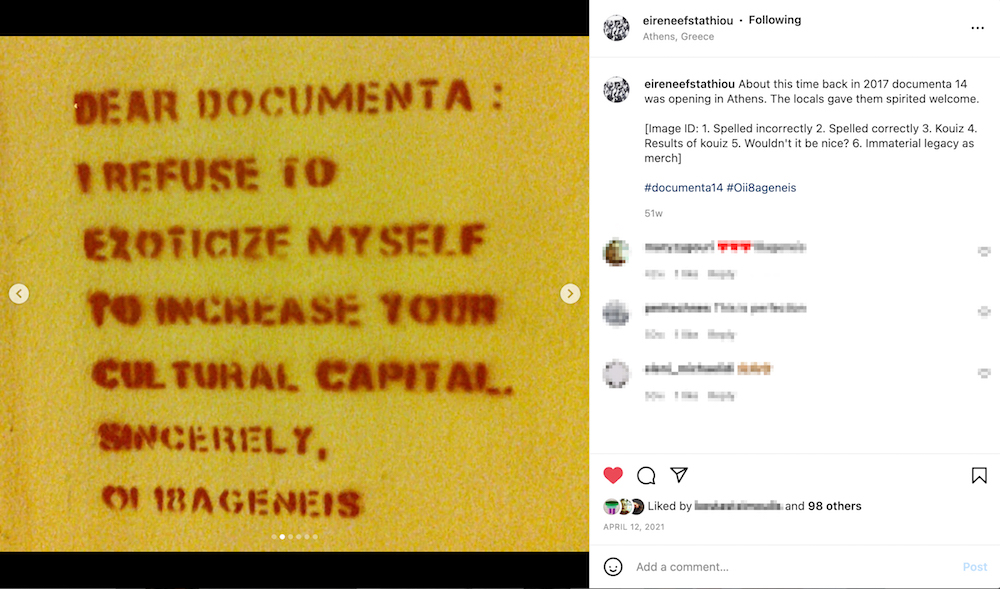

Following several informal conversations, Efstathiou, having only publicly taken credit for the project weeks prior by way of a modest Instagram post (fig. 3), agreed to a formal interview on the project’s origins, context, and trajectory. That conversation, which unfolded one July 2021 evening in Exarcheia, forms the basis for this text.

Figure 3. Instagram post from April 12, 2021 subtly claiming responsibility for the Dear Documenta project. Here pictured: the first stencil “spelled correctly” at circuits + currents. Courtesy Eirene Efstathiou.

“Not Anymore of This:” The Indigenous Assemble

The format-giving first stencil, Efstathiou emphasizes, was the result of a collaborative process, an ongoing conversation among a group of friends—artists and “cultural critic people”—grappling with the implications of documenta’s fraught arrival in Athens, “the city that,” as per artistic director Adam Szymczyk, “has become emblematic of contemporary crises” (Szymczyk 2017: 14). Echoing the wider critical consensus consolidating at the time, the group took particular issue with the extractivist impetus of the exhibition’s thematic proposal, which Efstathiou elsewhere likened to being “learned at.” In our conversation she recounts: “We were responding to the whole Learning from Athens thing. We figured out early on that there was something problematic about this type of learning, learning from us without actually asking us anything. We weren’t really being addressed as local scene or local producers, and all the address was mediated through big institutions, some of which it worked with and some of which it didn’t. They squandered a lot of goodwill from the scene by not having that conversation with people.” It is from this sense of disjuncture that the refusal to participate in the abstraction of Athens into a symbolic object of contemplation for an international contemporary art crowd was articulated.

The first stencil gave expression to a mounting resistance to becoming a “subject of observation,” a phrase Efstathiou offers while recalling an anecdote of her partner at the time experiencing “some art hipsters observing me while I was drinking coffee, as if [I was] also part of the exhibit.” Undergirding this sentiment was a wider ambience of mental fatigue with the exceptionalization of the crisis city Athens in the aftermath of “six years of being subjected to the neo-colonial biopolitics [of austerity], on the street, demonstrating every single day, involved in squats and solidarity. The thing that they thought was sexy”—and precisely what conferred cultural capital onto the city and its inhabitants—“had an emotional [boundary]. Not anymore of this, was the feeling.”

The slogan’s framing elements, the direct address “Dear documenta” and the “Greeklish” signature “Sincerely, Οι ι8αγενείς [the indigenous],” coined by performance artist Mary Zygouri, later invited to join the documenta 14 artist roster, were meant to add some levity, signaling the style of a “formal but polite letter” (the suggestion of adding an expletive PS was “unanimously rejected as rude”). If the address spelled an act of interpellation (“I guess I interpellated them, they were hailed. They noticed. I know for a fact that they definitely noticed.”) the signature contained a broader prompt: a prompt to engage with the idiosyncratic grammar of Greeklish, and a prompt to reflect on the exhibition’s contradictory (at times “kind of problematic”) alignment with post-colonial aesthetics vis-à-vis its own relationship to Athens. “That was the joke,” Efstathiou notes, “that they had come with mirrors and beads, and in reality, we weren’t going to get a smallpox blanket, but we weren’t getting the mirrors and beads either.”

In an editorial email exchange in April 2022 Efstathiou adds the following reflection on the gradual expansion of the signature’s meaning along with the unfolding of documenta: “I think that the signature started as a feeling about how the documenta 14 curatorial team approached Athens but then, once the exhibition was up, carried over into a critique of how the show itself dealt with various issues of indigeneity, their occupation with which was never really resolved in the show or its accompanying texts—perhaps with the exception of Denise Ferreira da Silva’s essay. I think they dealt with it about as well as they dealt with being in Athens: they tried but there were problems. I don’t know that this is really addressed by the stencils beyond the signature, but I definitely had a sense that we nailed it there.”

Once the slogan and format were crafted, Efstathiou produced the stencil and strategically placed it in three locations: the main venue of the 2015-17 Athens Biennale, then a named collaborator of documenta; at Omonoia Square, across the offices of documenta in Exarcheia; and on nearby circuits + currents, the project space of the Athens School of Fine Arts. Notably, the final location received a “spell-checked” version of the original stencil, which had read “exotisize” [sic]—to the equal amusement and exasperation of a post-colonial and performance studies scholar who had participated in its conception (fig. 3). The small distribution, somewhat at odds with the reproductive affordances of the medium, was a deliberate decision intended to actively center the capacities for “infinite representation” via participatory social media sharing. “It worked, I think, more than anybody expected.”

“More to Say:” Budget and Κουίζ

Following the resonance of the first stencil, two additional pieces appeared under the ι8αγενείς imprint once documenta’s tenure in Athens was officially inaugurated in April 2017. Both were created by Efstathiou: “I sort of just took the signature and decided I have more to say on the matter. And I would always check it with various people, to see if they thought it was okay. Those stencils I had machine cut, because it’s actually a lot of work to cut a stencil. So Striligas, a famous Athens copy shop, was involved. And they had printed things for documenta, so when I came in they said: ‘Oh, we’ve done several things for you!’ and I had to clarify that I’m not ‘them.’”

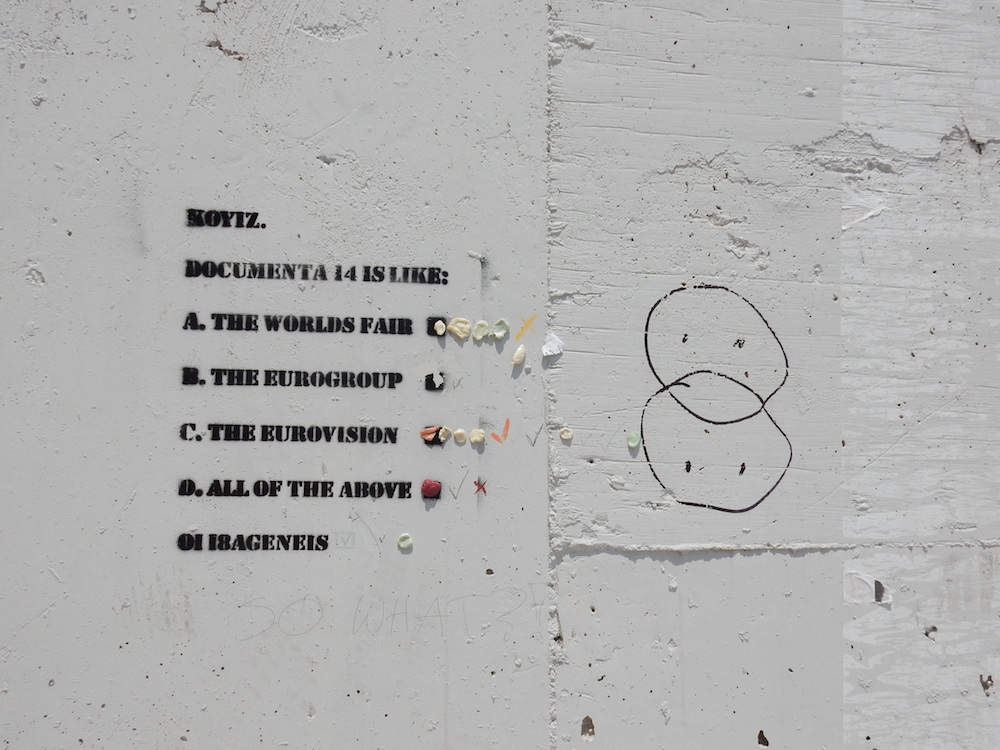

Figure 4. “Κουίζ. Documenta 14 is like A. The World’s Fair B. The Eurogroup C. The Eurovision D. All of the Above.” Stencil placed near the entrance of EMST. Photograph by Julia Tulke.

Stylized as a multiple-choice poll, “Κουίζ [quiz]” (fig. 4) placed documenta 14 into the wider cultural context of colonial exposition (the world’s fair), kitsch and popular spectacle (Eurovision) and crisis management (Eurogroup). Placed near the entrance of documenta’s main exhibition venue, the sleek National Museum of Contemporary Art (EMST), the execution of this stencil required a more “clandestine” approach, a hoodie-and-scarf-clad late-night operation realized with the help of a friend “who isn’t at all into clandestine shit.” In situ, the work took on an “unexpected but welcome” interactive quality, with passersby casting votes with chewing gum and markers. At the time I first photographed it, Eurovision held a firm lead. Efstathiou and I would have both voted “all of the above.”

The final piece addressed, once more, documenta’s inherently contradictory position: in professed alignment with anti-capitalist critique yet propped up with the abundant financial resources of a renowned international art institution: “It must be nice to critique capitalism etc. with a 38 (70?) million Euro budget” (fig. 5). The parenthetical interjection—“(70?),” a reference to one of the many documenta rumors going around at the time—registers a deep sense of suspicion, galvanized by the perceived opacity of the exhibition’s mode of operation. Unknowingly, it also anticipated documenta’s forthcoming brush with bankruptcy due to financial mismanagement on the part of Szymczyk, a delicious inversion of the moral discourse of fiscal (ir)responsibility that had so dominated public discourse about Greece’s so-called sovereign debt crisis through the years prior. Two iterations of the stencil appeared on the campus of the Athens School of Fine Arts, another documenta exhibition venue: “They were easy to do. I went down during one of the festivals, I think it was an anarchist festival, and the people kind of looked at it like, ‘oh…boring.’ It was not about the revolution, so it was a little bit boring.”

Figure 5. Budget, stencil at Athens School of Fine Arts. Photograph by Julia Tulke.

If not the revolution, Efstathiou’s carefully placed interventions joined a wider chorus of street level dissent with documenta’s presence in Athens, including the mischievous Crapumenta series and several playful variations on the theme (Earning from Athens, Learning from Capitalism). Her own favorite response—“I like it more than my own project”—was #Rockumenta, in which a group of LGBTQI refugees “stole” a participatory art piece by Catalan artist Roger Bernat, titled “Replica of Oath Stone.” The group had accepted a formal invitation (and 500 Euros) by Bernat to participate in a mock funeral procession of the stone he had choreographed, but instead staged their own performative abduction, framed by an open letter condemning their instrumentalization in the work: “Your rock is supposed to give us a voice, to speak to our stories. But rocks can’t talk! We can!” (fig. 6). The artist’s response, per Efstathiou, “revealed everything that’s wrong with supposedly community-engaged projects that don’t genuinely engage with the community. His response was just bad: he was pissed, and then he just got a new stone.” It is the very simplicity of the intervention that denotes its brilliance for her: “You always wonder how you can make a rupture in art institutions and #Rockumenta showed that it’s not so hard. The limits of the tolerance of the institution to actual politics or difference are inscrutable but easy. If you find the brackets, it’s easy to make a little explosion.”

Figure 6. LGBTQI Refugees with “Replica of Oath Stone” at the Polytechnic University of Athens. Image courtesy of LGBTQI Refugees Greece.

Immaterial Legacy and Claiming the Project

The final piece of the dear documenta series—the stenciled canvas bag Efstathiou had showed me during our first encounter—was created after d14 had concluded its tenure in Athens but before the exhibition closed in Kassel: “Well, what do you get, when you go to an art exhibition, a biennale or whatever? You get a tote bag. So everybody has many, many tote bags. So first I wanted to do, ‘my hometown went to documenta and all I got was this crappy tote bag,’ referencing these t-shirts that were everywhere in the 1990s: ‘my sister went to Disney world and all she got me was this crappy t-shirt.’ But then I remembered that Szymczyc had actually said ‘we’re leaving this immaterial legacy.’” Five years on, it is obvious that “their immaterial legacy didn’t last that long.”

Already limited by its confinement to the field of contemporary art—“the lowest rung of the ladder” in Greek cultural production—documenta’s presence in the city was largely imperceptible to the general public (“people didn’t know it was here, nobody cared”). But even within its very milieu, documenta failed to inaugurate any meaningful changes with regard to the severely precarious conditions under which contemporary artists live and work in Greece, which have only recently begun to incrementally improve due to the efforts of self-organization. Things could have been different, says Efstathiou, “if they had actually implemented some of their Marxist discourse, if there had been redistribution—of cultural capital, of money, of network, or even just a space,” opportunities for which were diminished by the lack of local interest in continuing volunteer collaboration with documenta people living well on “foreign salaries.”

Figure 7. “Immaterial legacy as merch” in the post-documenta era.

Mobile and small-scale in distribution (“it was exclusively a gift, I didn’t ever sell it”), the tote bags received considerably less attention than the prior stencils, an artifact, perhaps, of the ephemeral import of documenta itself. “But in the immaterial legacy time, the post-documenta era, several people carried”—and continue to carry—“them around” (fig. 7). Appearing in random contexts throughout Athens, the DIY merch—a counterpoint to the officially authorized drawstring bag, socks, and belts sold by documenta—can be assumed to have yielded some instructive misunderstandings. Efstathiou herself relays an encounter to that very effect; at an event in the exhibition’s immediate aftermath, the closing conference for the research project “Learning from documenta,” one participant, a young German woman, noted her tote bag and excitedly asked if she was from Kassel—a misreading that serves as just “another reminder of how myopic the art world often is.”

As for claiming the legacy of her own project, five years from its inception and four years from documenta, Efstathiou offers the following at the close of our conversation: “The reason not to claim it then, was that me and the other collaborators, didn’t want it to look like a self-promotional thing. We wanted to keep our critique outside of our positions as artists towards the show. Speaking for myself, I just wanted to address the show, I wanted to address documenta, with some concerns that I had with their inhabitation of Athens. And there was, in actual fact, no other venue to do that, no unmediated venue. And why would I claim responsibility now? Because I’m kind of proud that I did it, together with many other collaborators. And since people keep asking, I thought why not. Αυτά.”

REFERENCES

Szymczyk, Adam. 2017. “14: Iterability and Otherness—Learning and Working from Athens.” In: Quinn Latimer and Adam Szymczyk (eds.) The Documenta 14 Reader. Munich: Prestel.

Eirene Efstathiou is a visual artist working in a variety of different media from painting and printmaking to performance to small scale installations, her practice investigates collective and archival memory, sentiment, affect and how these function in the public sphere. She is a graduate of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Tufts University, and the Athens School of Fine Arts. Efstathiou has participated in numerous solo and group exhibitions in galleries and museums in Europe and the United States. She is the recipient of the Deste prize, Onassis, Neon, and Artworks grants for research and study. Her work is represented in public and private collections in Europe and the United states. She lives and works in Athens, Greece. https://eireneefstathiou.com/

Julia Tulke is a PhD candidate in Visual and Cultural Studies at the University of Rochester, NY and the 2021-2022 Pre-Doctoral Fellow at Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Her research broadly interrogates the politics and poetics of space, with a particular focus on crisis cities as sites of cultural production and political intervention for which Athens has figured as her central case study. Her work on the city through the past decade includes research and writing on political street art and graffiti, austerity urbanism, crisis photography, and the emergence of feminist and queer protest. Cumulating and concluding these endeavors, her dissertation traces the proliferation and significance of artist-run spaces and initiatives during the historical period bounded by the 2008 economic crisis and the 2020 pandemic emergency. https://juliatulke.com/

related

- Exhibiting a Media Ecology of Crises: A Visit in the Thessaloniki Cinema Museum

- The Intricate Thing Called Art

- Recollecting History, Bodies and Looks: the Graphic Novel Bandits (Part 1) by Yorgos Goussis and Yiannis Rangos

- What could art history contribute to modern Greek studies in the 21st century

- VIDEO: What Greece...?