The Fall of the House of Commons

A Sci-Fi opera based on material from an ever-closer reality

24 May 2021

Alekos Lountzis, Orestis Papaioannou

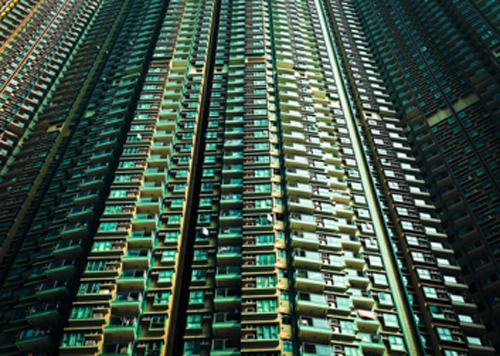

The city breaks up into pieces from an incomplete jigsaw puzzle.

Each piece of the jigsaw is a miniature ghetto.

For those outside, the people inside are always, all of them, contagious “miasmas”;

for those inside, the people outside are always, all of them, preying “suspects”.

The universe of the ultra-modern metropolis has increasingly come to resemble some repressed past—the cracked image of its genealogy, no longer allowed to reflect itself on artificial lakes.

Social classes have become hygienic zones, neighbourhoods have become fortresses, borders have become barricades. Modern living is completely private, water- and air-tight, inoculated; all of it can fit inside a matchbox. All goods are home-delivered, all relationships are formed and broken inside buildings, all fantasies stop at the entrance mat and the doorman’s cubicle.

The moment before it collapses, the self-sufficient universe of this iconic House reaches a precarious balance as one jammed drawer in a suspended edifice of monstrous proportions. It’s the most common of apartments—hearth and kingdom of all that’s left of the social common(s). It’s both the house and its tenants, taken together. It’s the timeless theme that has chewed up and is now regurgitating all themes (cf. Poe’s “The Fall of the House of Usher”[1]).

And yet, all filters seem to be riddled with holes; all ghettos face the swelling tide; those inside yearn nostalgically for the outside, those outside want to penetrate in; all “Commons” (those on the inside) have given up part of themselves to “Randoms” (those on the outside), all “Randoms” would gladly give up some part of themselves to live the life of “Commons”. Or so they all think…

Of Commons and Randoms,

Of mice and men

There is no comparison,

There was never past tense;

There is only the present,

Only us and them.

When the hour comes for them to mix and mingle, even for a brief while, in a moment of desperate need, all limits and borders become fluid, all fantasies suck on the thumb of an ever-closer reality; some of them are already real, and some are part of this work…

The Fall of the House of Commons

Contemporary Opera –work in progress– (2019-2021)

Composer: Orestis Papaioannou, Concept & Story: Alekos Lountzis

Libretto: Alekos Lountzis - Orfeas Apergis (co-author in the English version)

Inspired by: Edgar Allan Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

“Perhaps the eye of a scrutinising observer

might have discovered a barely perceptible

fissure, which, extending from the roof of the

building in front, made its way down the

wall in a zigzag direction, until it became

lost in the sullen waters of the tarn.”[2]

Our starting point is an archetypal short story by a master craftsman, although largely underestimated at his time; a story which became a source of inspiration and a point of reference for numerous pieces of prose written by Poe’s literary descendants.[3] The Ushers have also had the privilege of getting many transcriptions and adaptations for the operatic stage,[4] the most well-known of which is probably the unfinished one by Debussy, who writes in one of his letters: “I live of late inside ‘The House of Usher’. […] It cultivates inside one the strange habit of eavesdropping upon what masonry stones may have to say, as if they were conversing with each other, and of expecting houses to collapse into heaps of rubble, as if this were not only natural but also inescapable.”[5]

The Fall of the House of Usher is an exhaustively studied, continually “metastasising” work, minutely mapped to its last crack and fissure, including the one which proves to be the House’s undoing. The current emanating from “… the capital and capitalised FEAR, which builds up, is reviled, is revived and finally laid bare”[6] in the Ushers, has been conducted, in time, through the circuits of all the arts, from opera to the cinema, and has helped create webs of interpretation that its original creator would have found impossible to believe. The gothic House which guards, christens, and devours its occupants, incessantly monitoring their breaths and heartbeat, turned into an acute prototype and an entire genealogy, which has well outlived the last of the Ushers; it has left its mark on everything that has been written after it on the subject of house or common fears.

“There was always a minority afraid of something, and a great majority [afraid of everything,] afraid of the dark, afraid of the future, afraid of the past, afraid of the present, afraid of themselves and the shadows of themselves.”[7]

The interplay between disclosure and concealment, the balance of terror inside the house, became part of history and gradually crept through every crack and into every hearth; this uncontrollable and unchecked dissemination is the real starting point and motive for the present work. From this very fluid premise spring both music and libretto, charting, as they should, their own oblique paths. They set sail on waters well beyond the initial frame of intertextual reference, crossing landscapes as close to home as the wall separating us from the people next door, or the imperceptible sounds of the all-too-familiar other, which may well be just an echo of our own footsteps as we walk down the corridor.

The opera The Fall of the House of Commons aspires to describe, or at least sketch out, that elusive resonance that connects the uniqueness of Poe’s emblematic House with the commonest everyday house (thus bringing into sharp contrast concepts of the “sublime” and the “kitsch”); it also aspires to combine musical idioms ranging from classic operatic melodrama right up to the multi-stylistic, eclectic re-assemblages typical of postmodern music.

The plot unfolds over five scenes/episodes, centring on a broken couple (He and She) instead of Poe’s twins, a visitor (Danae or Her) who is the “double” of the lady of the house (She), and above all on an omnipresent and omni-presiding robotic personal assistant, who keeps a record of the House’s memories, the conflicts of its occupants, and the whole symbiotic crossword.

The couple lives, continually constructed and deconstructed, under the watchful—and, when necessary, intervening—digital eye of a virtual yet human-like third party, an entity that simultaneously belongs and does not belong to the house, expressing itself through a computerised digital voice. Despite this not so improbable yet still quite peculiar state of affairs, we form the impression that a ghostly balance has been reached inside the House, which seems to be holding firm even as it is being put to the test by She’s illness. The arrival of a real third party, though, shakes the house to its foundations; the house ushers in (pun intended!) a new state of affairs, revealing cracks and lowering the melting point of all materials. The encasement (or entrapment) inside a space where all needs and desires can be satisfied in ritual ways (from 19th-century castles with their armies of servants, all the way to the endless digital services offered at the beginning of the 21st century) reaches its limits, self-perfecting, and at the same time (self-) destructing.

To conclude, this opera attempts to transfuse, not just to communicate, the sense of asphyxia felt in Poe’s iconic gothic House, into our homogenised present—no matter how we may subvert or underestimate it at times—in all its universal, price-tagged terror, its uniform tastes, its prefabricated fantasies. Further, the present work tries to turn to fruitful advantage its particular premise by projecting the atmosphere and feeling of Poe’s original story onto the only material nowadays found in abundance as this is methodically woven by the coming world of claustrophobia (or is it claustrophilia?) inside our very House. Our common here and now, digitalised and always within reach, untouched or adulterated through its use or abuse as the case may be, yet constantly palpable. Needless to say, this “common here and now” often manifests itself in not always self-evident political ways. The dysfunctional House presented by this opera might also then be thought of in terms of a “parliamentary dystopia” (and staged accordingly), in which case the House occupants and their robotic assistant could well acquire allegorical counterparts in the shape of all-too-familiar political figures or even entire countries. Greece which has been popularly presented or projected as a model of a damaged machine or at least a machine out of order, was a familiar prototype and a mirror at the same time.

Eventually, the focus of the opera in not on the robot/cyborg itself, but rather on the prospect of human-like machines and the ever-closer reality of machine-like citizens in this under construction universe, blurred as it emerges and interweaved with new ethical and social dilemmas, new habits and ways of understanding and relating to people and objects.

NOTES:

Alekos Lountzis studied law, communication, and social anthropology in Athens and Cambridge. He works in mental health. He writes poetry, prose, lyrics and opera libretti. His book Propaganda (2015) was awarded the Anagnostis Prize for Debut Poetry Collection. His book The Next Us was recently published (May 21) by Stigmos.

Orestis Papaioannou is a composer and performer. He has studied MA in Music Science/Composition at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and Lübeck University of Music and is currently a doctorate candidate at the Hamburg University of Music and Theatre, researching on contemporary opera.