The contradictions of the nation-state:

a perspective from geography

17 April 2021

Ares Kalandides Manchester Metropolitan University and New York University, Berlin

Understanding the nation (and the nation-state) as a project of modernity, i.e., a historically contingent form, begs the question of its geographical conditions: if it appears at a certain moment in time, it is also established in certain places. The celebrations of the 200th anniversary of the Greek War of Independence is possibly a good moment to re-evaluate this double time-space contingency of the nation-state and formulate questions in the intersection between history and geography. Can geography add to the understanding of the nation and the nation-state, typically privileged fields of historical inquiry, and if so, what are the geographical concepts that can assist us in this endeavour?

From the very first moment, the creation of the new Greek state involved a series of inclusions and exclusions, which are with us until today. There are probably several ways to conceptualize this geographically, but I would like to focus on just a few possible approaches: firstly, on the concept of territoriality; secondly, on these of borders and boundaries; thirdly, on the concept of scale; and finally, on the interconnectedness of places. This all needs to be examined more closely.

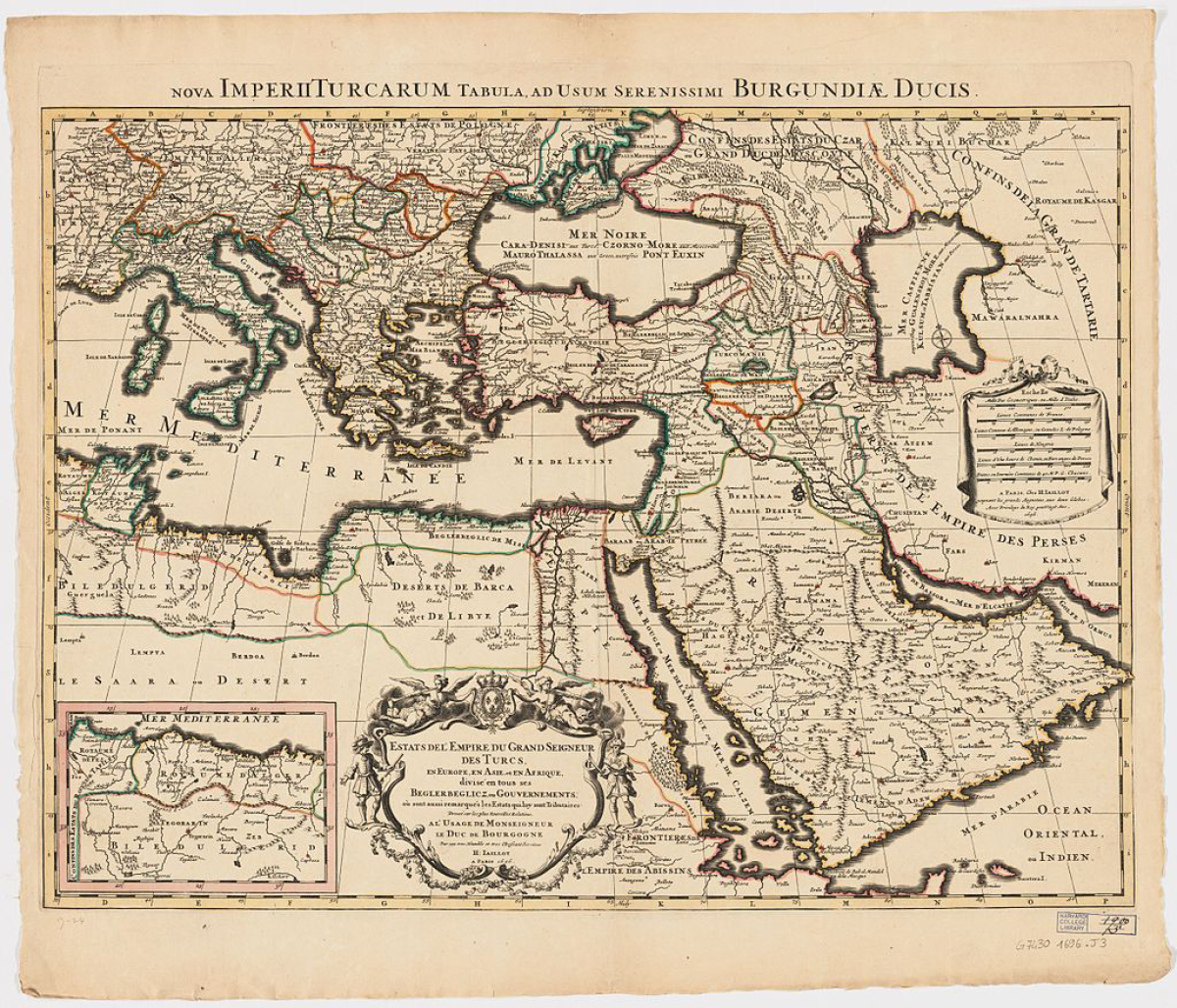

A state is territorial in many ways: it has its expansion over space and is defined by borders, which may or may not be contested. The power of the state is exercised inside these borders and the two are interlinked. One can argue that it is precisely the geographical extension of state power that defines state territory. What lies beyond state power is extra-territorial. Those who controlled the Greek state, after its birth in 1830, constantly sought to extend its territory, sometimes successfully other times not. This moving frontier of expansion is what always separated the inside from the outside of the new territorial formation. The consequences of the 1919-1922 Greek expedition into Asia Minor are a painful reminder of what a violent pushing of borders may mean for whole populations.

The nation, on the other hand, depends on the understanding of belonging together practiced by a group of people. This can be founded on a series of common characteristics such as language, history, customs, religion, political organization, or fights against a common enemy. The constitution of the modern Greek nation mobilised many of these features, at varying degrees. It also mobilised another concept, a spatial one: the real or imaginary homeland as a uniting element of nation-building. It was very real because it comprised the lands people lived on; and very imaginary, as it included “lost” territories of a legendary past. The nation, whilst not territorial per se, also has boundaries (here I oppose boundaries as social division lines to the physicality of borders). Just as borders define the inside and the outside of the state, so too do social boundaries define the nation: inclusion and exclusion is what creates the nation in the first place.

Nation-building and state creation are not necessarily simultaneous (in time), nor do they necessarily overlap (in space). The later means that territorial (state) borders and social (national) boundaries do not inevitably coincide, a discrepancy that may create political tension. Expansive invasions (externally) and displacement or ethnic cleansing (internally) are then used to bring the two together by force. The creation, expansion, and partial retraction of the Greek state in the 19th and 20th centuries illustrate attempts to resolve this tension in the most dramatic way.

On the one hand, there is the illusion of homogeneity in the territorial dimension. Even inside Greece’s moving frontiers, certain ethnic and religious groups were included in the nascent nation, while others were not. The very different ways in which Arvanites, Chams and Jews were incorporated over time in a nation that imagined itself in terms of a Greek-Orthodox Christianity, adequately illustrate this argument, raising questions of belonging.

This double articulation of inside/outside – between a territorial state and an imagined nation – is both fragmented and dynamic. This means that nation-states incorporate social groups in very uneven ways, in a process that may change over time, often after fierce confrontations. This unequal incorporation may be institutional, with certain groups formally barred from enjoying particular rights, be it civil, political, social, cultural or economic (e.g., women’s suffrage, LGBTQ+ rights, minority languages); or it may entail exclusion in everyday practices: discrimination, violence, and other types of practiced segregation. Citizenship in this sense is always an uneven and incomplete spatial process.

On the other hand, there are illusions of grandeur where the imagined nation transcends the borders of the state, includes faraway places, legendary former empires, and influence areas. Spatial discontinuity is by no means a hindrance in this undertaking. Constantinople or Alexandria are spaces that are thus incorporated into the imagined Greek nation, although they are outside the territorial state. The Byzantine expansion from southern Italy to the Levante has probably been historically the most pervasive expression of this idea, i.e., of an extended Hellenic space, for modern Greeks. Today, the recurring focus on a Greek diaspora in the USA, Australia or other countries of immigration produces a fantasy of a nation that spans the planet. Indeed, the idea of diaspora itself, so popular among Greeks, stresses the scalar contradictions between the reality of the territorially limited state and an imaginary global nation.

Scale, a further key concept in geography, can assist us with a second endeavour, too: this of understanding the interconnectedness of places. It allows us to think of the Greek Revolution and later nation-state, not in isolation, but as the outcome of the interlocking of several scales on a single territory. Some of the forces that brought the revolution about were very local, and had to do with regional social relations and conflicts; others (zooming out) may have to do with internal contradictions of the entire Ottoman Empire and its decline; others again (zooming out more) may have to do with the orientalist imagination, the colonial project of western European powers or the imperial ambitions of the Tsar; other forces may bring with them ideas and aspirations from faraway places, from the French and American revolutions; finally (zooming out once more) we could be looking at the outcome of integration struggles in a globalizing capitalism which is increasingly seeking to incorporate more territories into its worldwide reach.

In geographical terms, this means that we may sometimes need to look at England, Russia, India or even Haiti and the United States of America to understand what is happening in the Eastern Mediterranean at the beginning of the 19th century. All the above forces, that operate at different scales from the very local to the global, and in different places simultaneously, come together and interact on this small piece of the earth at this particular moment in time that we are examining, producing differentiated and dynamic outcomes: Greek nation-building, the 1821 revolution, and the creation of the modern Greek state. They also still come together today in the ongoing discussions on Greek-ness, identity, belonging and citizenship – on the inside and outside of the Greek nation.

Ares Kalandides is Professor of Place Management and teaches geography at Manchester Metropolitan University as well as history and urban studies at New York University (Berlin). He is co- editor of the “Routledge Handbook of Place” (2020) and the forthcoming “Gendered transformations of space” (in Greek).