The Body that Deconstructs

13 May 2021

Adrianne Kalfopoulou Davidson College

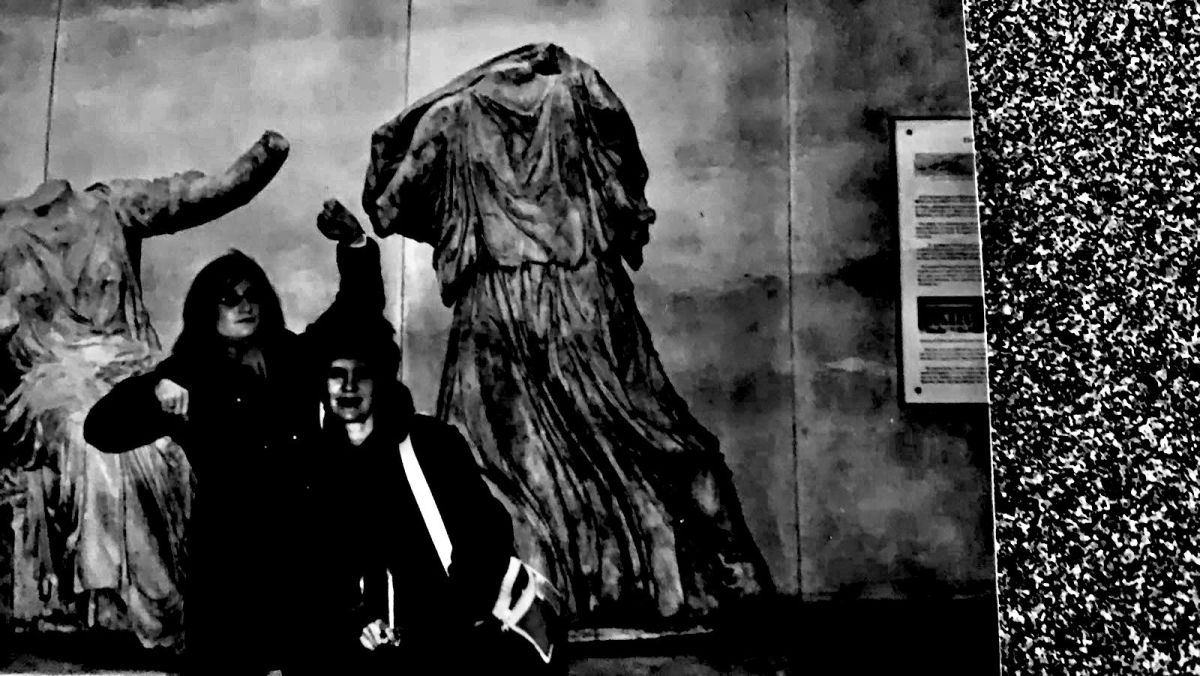

Greece (de)constructs belonging. Greece as classical paradigm in the gaze of the German Romantics, as Golden Age ideal in the gaze of nations supporting its struggle for nation-building, a yearned-after homeland in the gaze of the diaspora, sapphire-colored sea hugging a geography’s contours in the gaze of those who wish to stretch their own bodies on its beaches. But what body is Greece to itself? What Greece as it shapeshifts under the multivalence of its histories, the lecherous eyes of empire disrobing its monuments and thieving its marbles, a Roman envy that transported treasures from Delphi, a Christian violence that lopped off marble phalluses, a British desire for antiquity that found a Lord suffering from syphilis (apparently his nose deformed by the disease), lusting after friezes as he plotted ways to get the massive slabs to England – weighty as they were so many sank in the crossing: perhaps Greece is a parable about the voraciousness of desire and of the colonizing eye.

What Greece is left after the invasions and occupations, after the thefts and projections? “Live Your Myth in Greece,” said an ad on bulletin boards on the highway to the Eleftherios Venizelos airport. On arrival such ad was one of the first things any visitor might see, part of an expensive campaign the Greek National Tourist Organization promoted after the 2004 Olympic Games. When the debt crisis broke out, the slogan was scrawled in graffiti (usually red) over many of Athens’ city surfaces and shuttered businesses, often turned into “Leave Your Myth in Greece”; live and leave your myth in Greece, as so many have done. Think of Byron, the passionate advocate he was for Greek nationhood: he joined the war and, in helping the Greeks resist the first sieges of the Ottoman Turks in Missolonghi, a strategic port town in Western Greece, Byron died of fever at the age of 36 in 1824. His name etched into the cultural imaginary as deeply as the letters he carved into the marble of a broken column at the Temple of Poseidon in Sounion.

“I woke with this marble head in my hands; | it exhausts my elbow and I don’t know where to put it down”, says the speaker in George Seferis’ Mythistorema,* detailing an inability to separate from this detached head, that was “falling into the dream, as I was coming out of the dream.” This makes it hard to distinguish a self apart from this marble head, and it becomes suddenly impossible to differentiate the head’s physical challenges, or amputations, from that of the speaker’s:

Finally, the speaker’s hands, implicated as they are in holding this head, “disappear and come towards me/ mutilated”.

Maybe we need to embrace more of the country’s lopped off heads, its ruptures, and castrated statues. Maybe, like this stanza from Mythistorema, we should let the story of “the mouth that keeps trying to speak” have its trauma: the myriad ways Greece has been objectified has broken it into a body of bodies, of restless pieces. In his poem ‘The Second Coming’, W. B. Yeats tells us famously, “Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold”. A modernist and a Nobel laureate just like Seferis, Yeats liked to look backwards. But writing later in the century, Seferis, like Eliot, seems to understand the waste land is its own reality, “falling into a dream…” The real horror, or continued danger, is that we pretend we are whole, that none of this has happened, that “the centre” can in fact hold, and the marble head in our hands has nothing to do with us. Worst of all would be to pretend that our hands have not been mutilated.

* George Seferis, Mythistorema, translated by Edmund Keeley. See https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/51457/mythistorema

Adrianne Kalfopoulou is the author of three poetry collections, most recently “A History of Too Much”, and the essay collection “Ruin, Essays in Exilic Living”. She currently serves as the McGee Professor of Creative Writing at Davidson College.