Essentially white;

or, why do looters always return to the scene of the crime

11 November 2022

Dimitris Plantzos National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

According to a new agreement announced, rather unexpectedly, last July, between the Greek Ministry for Culture and American billionaire businessman and collector Leonard N. Stern, 161 ancient artefacts from Stern’s private collection are to be returned to Greece, following a 25-year long period during which they will be shown at the Metropolitan Museum in New York. According to the complicated provisions of the deal, starting January 2024, the Met will house the entire collection on long-term loan from the Greek government for 10 years, after which “select works will periodically travel to Greece over 15 years for display while other loans of Cycladic art will come to the Met”; following that 25-year loan period, “important works” of Cycladic art will continue to be loaned to the Met from Greece for an additional 25 years, subject to the Greek government’s consent at the time, thus bringing the end of the whole operation well into the 2070s. To kick-off the deal, a selection of 15 pieces was agreed to be sent to Greece, to be displayed in Athens for a single year (until October 2023).

If the deal outlined above – a “mess” according to one of its international critics – reads like an exchange of hostages, well, this is because it is: if, for example, the Greek state chooses to discontinue the agreement after the first 25-year period (in 2049), then a selection of 122 pieces from Greece would have to be sent to the Met in their place, for the remaining 25 years prescribed in the agreement.

The artefacts in question belong to the so-termed by archaeologists “Early Cycladic” (or simply “Cycladic”) culture. Active on the Greek islands of the Cyclades between c. 3200-2000 BCE, this apparent “civilization” remains virtually unknown to us, save for a multitude of artefacts produced in marble, predominantly flat or round vessels and, most sensationally, human figurines, habitually female, in a variety of sizes. Because of their increasing value as collectors’ items, Cycladic figurines and vessels, like those in the Stern collection, have been systematically excavated illicitly and exported from Greece, mostly between the 1950s and the 1970s. As Cycladic artefacts were never exported in antiquity, they are highly unlikely to be found, say, in present-day Italy, Turkey or Syria, where some other types of Greek artefacts were taken already in antiquity (namely Greek vases, whose provenance is notoriously difficult to prove once they have been looted away from their original contexts). In other words, any Cycladic artefact now seen anywhere in the world is almost by definition the product of an excavation on Greek soil.

The agreement signed by Greece and Stern, allows the collector to “donate” his illegally acquired artefacts to a private foundation created by him, so that he can take advantage of the generous tax reductions offered by the US state to philanthropists and benefactors donating to cultural causes. Two museums, the Met and the Athens-based Museum of Cycladic Art (a private institution founded in the 1980s by another antiquities collector, Greek shipping magnate Dolly Goulandris), were appointed by the agreement as the intermediaries in the transaction, since they will provide the venues where the 161 pieces will be exhibited, on rotation, for the rest of our lives (and more).

Although Greek authorities celebrated the “repatriation” of the 161 “masterpieces ... of unique archaeological and scientific value”, claiming that the deal spared Greece a “messy court battle”, many independent observers, both at home and abroad, failed to see the reasons for this enthusiasm (especially since the whole process has been designed to be so lengthy). Several collective bodies, including the Departments of History and Archaeology at the Universities of Athens and Crete, as well as the Union of Greek Archaeologists, issued public statements stating the obvious: that, for one, the 161 antiquities are the product of illegal dealing and trafficking and that both Stern himself and the Metropolitan Museum are already under pressing scrutiny for repeated cases of looted antiquities dealing even in the recent couple of years; that even at a quick glance one can spot within the collection pieces that may be proven beyond any reasonable doubt to have been illegally exported from specific sites on the Cyclades; and that, finally, many of the pieces in question might well be fakes.

Faking a Cycladic artefact is not as difficult as it might seem, as it merely requires some skill and the necessary know-how, quite accessible by now to scholars and copyists alike, as well as some considerable amount of time for the newly made “antiquities” to be appropriately patinated and “antiquified”. Private collections of Cycladic art worldwide may easily be shown to contain a considerable amount of fakes, recently made so that eager and untrained collectors may be duped into wasting their dollars on junk. A small number of world-renowned elite scholars seem to have been contributing to this, by providing “authentications” or cleverly masking dubious provenances at will, a scholarly path they apparently turned into a lucrative line of business. Deciding to “repatriate” a collection of doubtful origin, undocumented provenance, and blindly taken for granted authenticity does not help the promotion of Greek antiquity; it only allows an American collector of looted antiquities to earn a hefty tax reduction worry-free. In view of these shortcomings, Prof. Christos Tsirogiannis of the University of Aarhus was quoted by the New York Post saying that “the deal is completely embarrassing and unacceptable”.

Besides the collection’s questionable authenticity, and unquestionably illegal status, one needs to emphasize that by signing this agreement the Greek government relinquishes the definite and permanent right of possession for the entire collection to a purpose-made “Hellenic Ancient Culture Institute” jointly governed by the Goulandris and Stern families. Even if the agreement states that Greece retains its lawful right of ownership, this is a mere façade: according to Greek and international law, Greece, as the country of origin, retains by default its right of ownership over any antiquities found on or in its soil, even if certain objects may be abroad (unlawfully or not) and even if for any reason the Greek Ministry of Culture chooses to recognize the right of possession of certain objects to private individuals or legal entities, such as private collectors and museums. This is presented most eloquently by clause B(f) of the signed agreement, stipulating that, in the year 2049, those items of the collection that happen to be in Greece at the time (following the rotational exchange described above) will be displayed “at the Cycladic Museum” or any other museum in Greece, as the Hellenic Ancient Culture Institute’s Board of Directors will indicate and the (Greek) Ministry will approve. The Institute will equally indicate where the remaining pieces may be exhibited if and when they are returned to Greece, be that in 2049 or even 25 years later (which takes us as far ahead as 2074).

Yet, this is not a case of a mere legal technicality. Not even a problem – however severe – of illicitly obtained antiquities, forever destroyed archaeological contexts, and forever lost historical data (a destruction that cancels any celebration of the “scientific value” born by the 161 artefacts: this has been forever rendered insignificant). The whole affair, and the triumphant opening of the exhibition of the first 15 “treasures” staged at the Museum of Cycladic Art on November 3rd, 2022, is a striking illustration of the ways Greek archaeology runs itself.

Cycladic figurines from the Stern collection in Athens. © Paris Tavitian (2022)

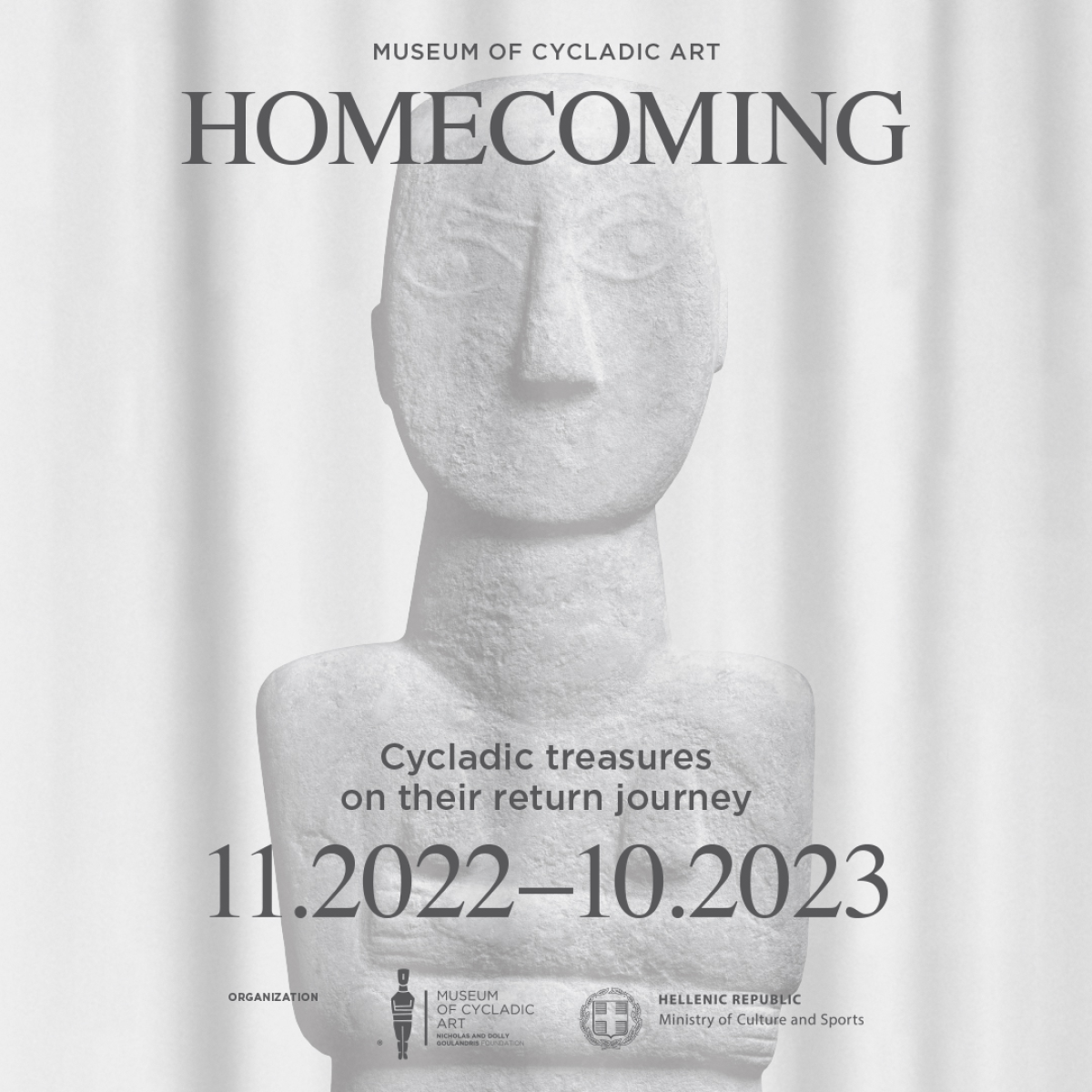

Titled “Homecoming”, and designed as an eery landscape of sterilized white fabrics and bleached surfaces, the exhibition ingeniously manages to combine the rhetoric of Theo Angelopoulos with the visual aesthetics of Yorgos Lanthimos – only as if in a parody of both. “Homecoming” obviously refers to the notion of “repatriation”, a narrative device invented by the Greek state in the 1960s or so, to enable private collectors of looted antiquities to “donate” their collections to the state while retaining their possession. This led to the creation, most notably, of the Museum of Cycladic Art, which despite its dubious origins has managed to operate as a bona fide art institution, especially while its founder, Dolly Goulandris, was still alive and active up to the mid-2000s. The very idea of “repatriation”, of course, romanticizes the stolen artefacts, and in effect personifies them into the nation’s long-lost brothers and sisters now seemingly on their way back from an involuntary exile. As a rhetorical scheme, “repatriation” glosses over the fact that illicit excavation and export of antiquities is an illegal activity, more often than not associated with and dependent on other criminal offenses such as forgery, theft, unlawful deceit, or even crimes against life. While it implies that there is a homeland waiting for their return, it allows for the stolen antiquities to serve as prized possessions of anyone wealthy and powerful enough to own them, and use them at will as cultural capital or even as monetary collateral. And when it does materialize, “repatriation” only helps launder these artefacts into “national treasures”, conveniently forgetting the fact that they are lost to science forever. It might be worth noting, for example, that one of the figurines now on show in Athens (actually the show's centerpiece) has already been included in a catalogue of Cycladic artefacts illicitly excavated on the Greek islet of Keros, published by the Museum of Cycladic Art itself, and its former curator, Peggy Sotirakopoulou (Sotirakopoulou 2005: no. 170). Although it is obviously the same piece (Stern Coll. no. 138 and no 11 in the current exhibition) no explicit mention of its previous ownership record is made.

Cycladic artefacts from the Stern collection in Athens. © Paris Tavitian (2022)

Whitewashing (literally) illicitly exported Cycladic artefacts, however, also operates on a different level: besides money, such “homecomings” launder bourgeois aesthetics and archaeopolitical narratives through a veneer of supposed high taste. An international class of venture capitalists thus emerge from the looted tombs (or the faker’s bench), all white and cultivated, imposing their reinvented values onto the collective imagination of a subordinate class also wishing to pass as sophisticated and cultured. And this, for a group of artefacts that were notoriously not white when originally used, but heavily painted with bright pigments in order to denote anatomical details or even abstract motifs and designs (Papadatos 2016). Having been ignored as “barbaric” and “primitive” for centuries, Cycladic artefacts (and especially the figurines) were born again as sophisticated objets d’ art by the modern sensibilities of the likes of Amedeo Modigliani, Alberto Giacometti, and Henry Moor (Chrysovitsanou 2004). At the same time, in about the interwar years, Cycladic artefacts were rehabilitated into the Greek national canon, where they remained ever since as paragons of Hellenic taste and artistic sensitivity. Ironically, all this for appearing white rather than colourful, since whatever pigments they once carried had long gone invisible.

An Instagram post by Max Hollein, Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (3 November 2022).

The exhibition’s unparalleled archaeopolitical cynicism is best exemplified by a post written by Max Hollein, Director of the Met, on his personal account on Instagram, on the night of the opening in Athens. In a shocking display of bad taste and excruciating first-world arrogance, he photographed the evening’s buffet – laden with a frightful assortment of Cycladic replicas, white table linen and white candles in the midst of any delicacies the museum’s caterer had to offer – commenting on how this project brings private collections “with complex provenances” to what he termed “the public sphere”. As far as meta-languages go, Hollein’s attempt to mask a series of criminal activities as a slightly unfortunate technical hitch is in perfect tune with the entire project, presumably designed somewhere in Manhattan’s Upper East Side, just to be presented to the ever-eager Greek natives to sign with zeal. I only wonder what folks will make of this photo in 2074.

References

Chrysovitsanou, Vasiliki. 2004. “Les figurines cycladiques: de la repulsion à la fascination”. In: Sophie Basch (ed.) Le Métamorphose des ruines. L’influence des découvertes archéologiques sur les arts et les lettres (1870-1914). Athens: École française d’Athènes, pp. 33-38.

Papadatos, Yiannis. 2016. “Figurines, paint, and the perception of the body in the Early Bronze Age South Aegean”. In: Maria Mina, Sevi Triantaphyllou, and Yiannis Papadatos (eds) Prehistoric Bodies and Embodied Identities in the Eastern Mediterranean. Oxford and Philadelphia: Oxbow Books, pp. 11-17.

Sotirakolpoulou, Peggy. 2005. The "Keros Hoard": Myth Or Reality? : Searching for the Lost Pieces of a Puzzle. Athens and Los Angeles: Museum of Cycladic Art and The J. Paul Getty Trust.

Dimitris Plantzos is Professor of Classical Archaeology at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. He writes on classical art and its modern receptions, archaeological theory, and the uses of antiquity in contemporary political discourse. He is the author of Greek Art and Archaeology and The Art of Painting in Ancient Greece, both published by Kapon Editions in Athens, Greece and Lockwood Press in Atlanta, Georgia in 2016 and 2018 respectively, and The Archaeologies of the Classical. Revising the Empirical Canon (2014) and The Recent Future. Classical Antiquity as a Biopolitical Tool (2016), by Eikostos Protos and Nefeli Editions respectively (both in Greek).